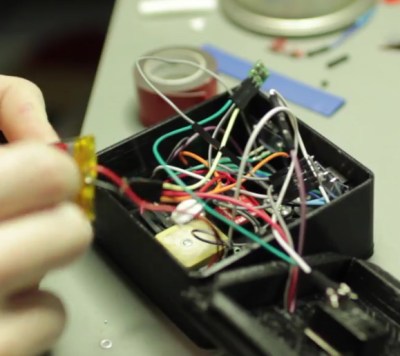

We’ve all experienced it: that sinking feeling you get when you’ve powered up your latest circuit and nothing happens. Maybe you made a mistake in your design or you shorted something while soldering. It’s even possible that ESD damaged one of your chips. All of these issues and more are possible, maybe even inevitable, when designing your own hardware.

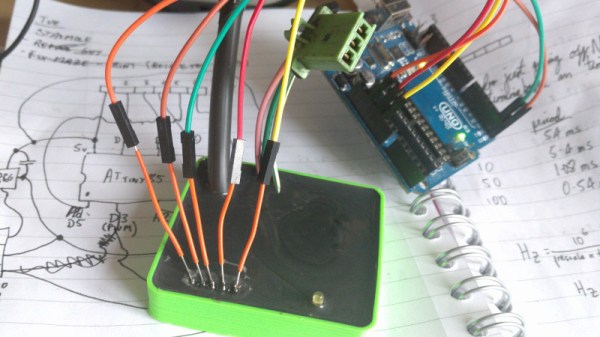

But what if your design is perfect and your soldering skills beyond reproach? What if your shiny new device is DOA but you’ve done everything right? A fascinating report by [Yahya Tawil] makes the case that it’s increasingly possible that you’ve run across a counterfeit component. While it’s still relatively unlikely the hobby hacker is going to get bit by the counterfeit bug, the figures and examples referenced in his report may surprise you.

[Yahya] points to a number of government studies on the rising scourge of counterfeit components, and the numbers are rather surprising. For example, the U.S Department of Commerce conducted a study between 2005 and 2008 where over 50% of respondent manufacturers and distributors had encountered counterfeit components. Another estimate claims that up to 15% of the semiconductors purchased by the Pentagon are counterfeit, presenting a serious risk to national security.

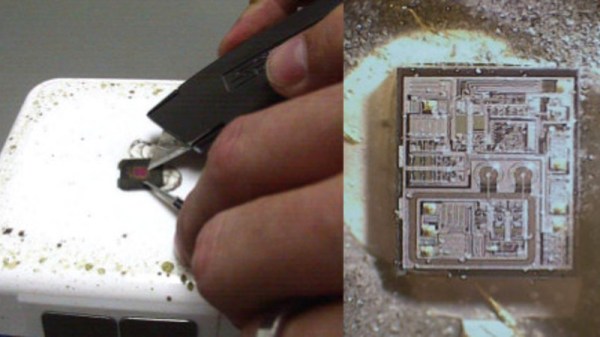

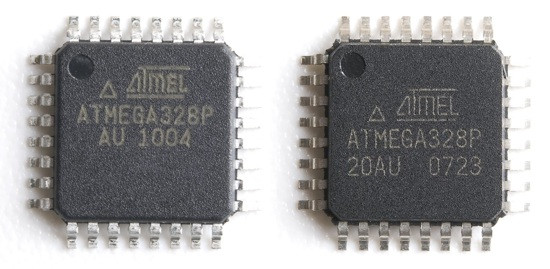

But how exactly does one counterfeit a microcontroller or transistor? Interestingly, in the vast majority of cases, old chips are pulled from recycled circuit boards and new labels are written over the original. Sometimes the forgery is as simple as changing the date code on the component or up-rating its capability (such as labeling it military spec when it isn’t), but in some cases chips with the same package will be labeled as something else entirely. Other tricks are decidedly low-tech: the documentation for the device may list functions and capabilities which it simply does not possess, artificially raising its value.

The report is a worthwhile read, even for those of us who may not be purchasing components in the same quantities as the Pentagon. It may make you think twice before you click “Buy” on that shady site with the prices that seem to good to be true.

Counterfeit components certainly seem to be on the rise from where we’re sitting. We’ve covered a number of other studies on this increasingly common trend, as well as first hand accounts ranging from successful recoveries to frustrating failures.