Electromagnetic fields are everywhere, all around us. Some are generated naturally, but in vast majority of cases, it’s we humans that are generating them with artificial, electronic means. Everything from your mobile phone to the toaster will emit some sort of signal, be it intentional or not. So we think it only befits the general electronics-orientated hacker to have some way of sniffing around for these signals, so here is [Mirko Pavleski] with his take on a very simple pair of instruments to detect both static and dynamic electromagnetic fields.

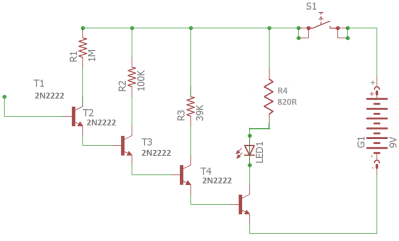

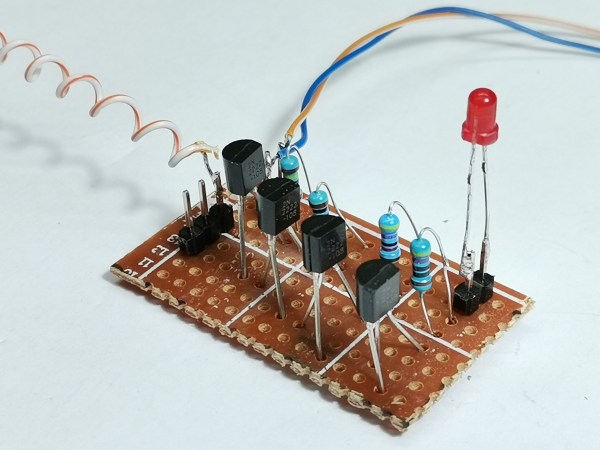

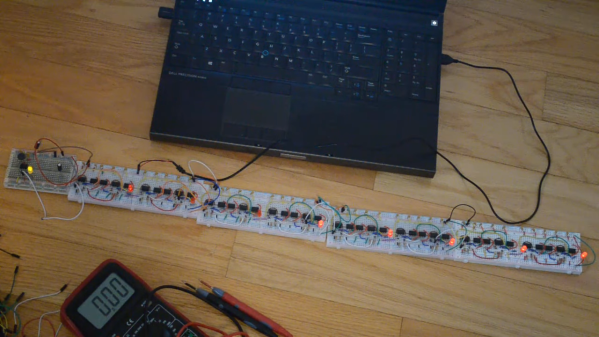

The first unit (a simple electroscope) uses a cascade of 2N2222 NPN bipolar transistors configured to give a high current gain, so any charge near the antenna will result in increasing currents in subsequent stages, finally illuminating the LED. Simple stuff.

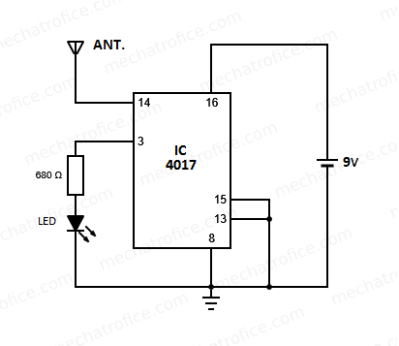

The second unit relies on the extremely high input impedance of the old-school CMOS 4017 decade counter, which is likely of the order of 100 MΩ or even more. Normally you would not leave such a CMOS input floating, or even connect it with too long a PCB trace — lest it pick up a stray signal —but for detecting alternating EM fields, this appears to work just fine. Configured as a simple divide-by-ten, when presenting 50 Hz AC, the LED can be seen to flash at 5 Hz.

Simple stuff, and this scribe has all those exact parts in the junk box, so will be constructing these shortly!

We’ve covered electroscopes for years, here’s a modern twist on a famous classic experiment, and some hair-raising experiments to get you started.

Continue reading “A Simple EMF Detector And Electroscope You Can Make From Junk Box Parts”

![USB to Dupont adapter by [PROSCH]](https://hackaday.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/2022-01-01-USB-to-DuPont-adapter-feat.jpg?w=600&h=450)