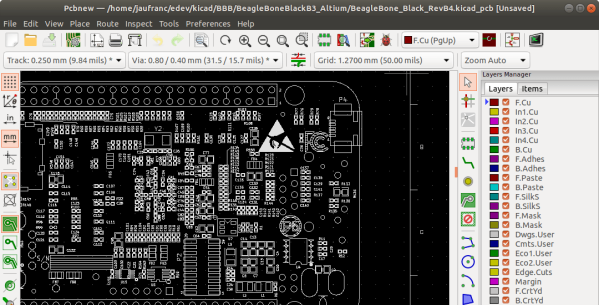

Around these parts we tend to be exponents of the KiCad lifestyle; what better way to design a PCBA than with free and open source tools that run anywhere? But there are still capabilities in commercial EDA packages that haven’t found their way into KiCad yet, so it may not always be the best tool for the job. Altium Designer is a popular non-libre option, but at up to tens of thousands of USD per seat it’s not always a good fit for users and businesses without a serious need.

What do you do as a KiCad user who encounters a design in Altium you’d like to work with? Well as of April 3rd 2020, [Thomas Pointhuber] has merged the beginnings of a native Altium importer into KiCad which looks to be slated for the 6.0 release. As [Thomas] himself points out in the patch submission, this is hardly the first time a 3rd party Altium importer has been published. His new work is a translation of the Perl plugin altium2kicad by [thesourcerer8]. And back in January another user left a comment with links to four other (non-KiCad) tools to handle Altium files.

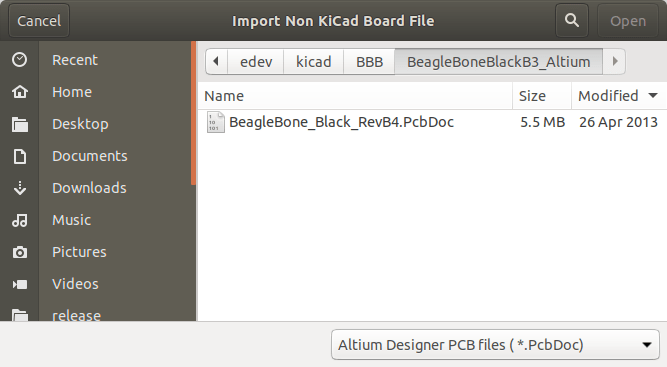

If you’d like to try out this nifty new feature for yourself, CNX has a great walkthrough starting at building KiCad from source. As for documents to test against the classic BeagleBone Black sources seen above can be found at on GitHub. Head past the break to check out the very boring, but very exciting video of the importer at work, courtesy of [Thomas] himself. We can’t wait to give this a shot!

Thanks for the tip [Chris Gammell]!