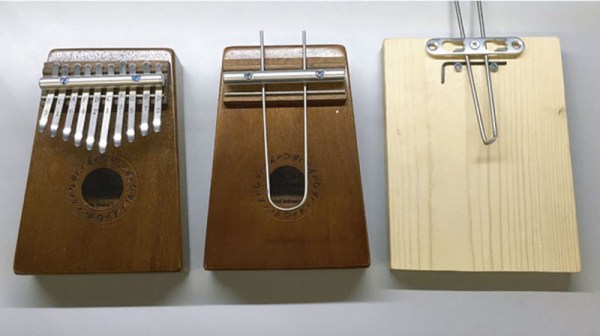

If your eyes are 20/20, you probably do not spend much time thinking about prescription eyeglasses. It is easy to overlook that sort of thing, and we will not blame you. When we found this creation, it was over two years old, but we had not seen anything quite like it. The essence of the Bear Paw Assistive Eating Aid is a swiveling magnet atop a suction cup base. Simple right? You may already be thinking about how you could build or model that up in a weekend, and it would not be a big deal. The question is, could you make something like this if you had not seen it first?

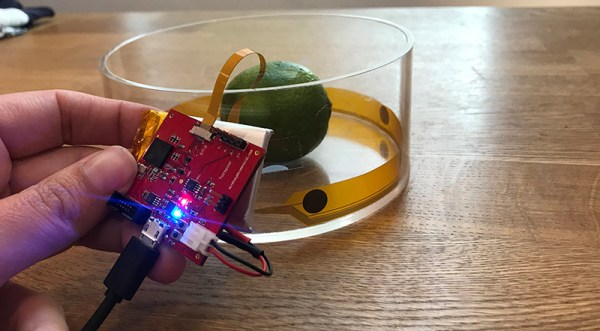

Over-engineered inventions with lots of flexibility and room for expansion have their allure. When you first learn Arduino, every problem looks like a solution for that inexpensive demo board and one day you find yourself wearing an ATMEGA wristwatch. Honestly, we love those just as much but for an entirely different reason. When all the bells and whistles are gone, when there is nothing left but a robust creation that, “just works,” you have created something beautiful. Judging by the YouTube comments of the video, which can be seen below the break, those folks have no trouble overlooking the charm of this device since the word “beard” appears 95 times and one misspelling for a “bread” count of one. Hackaday readers are a higher caliber and should be able to appreciate its elegance.

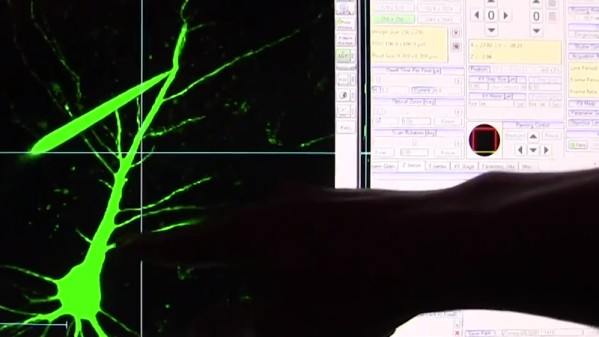

The current high-tech solution for self-feeding is a robot arm, not unlike this one which is where our minds went when we heard about an invention about eating without using hands, and we will always be happy to talk about robot arms.

Continue reading “Overlooked Minimalism In Assistive Technology”