It’s no secret that we here at the Hackaday are suckers for cool display. LEDs, OLEDs, incandescent, nixie or neon, you name it and we want to see it flash. So it fills us with joy to discover a new way to build large, daisy-chainable 16-segment digits, and even more excited to learn how easy they are to fab and assemble.

A cousin of the familiar 7 segment display, the 16 segment gives so many more possibilities (128% more possibilities to be exact) for digit display. To be specific, those extra segments unlock the ability to display upper and lowercase latin characters as well as scads of punctuation.

But where the character set is complex, the assembly is anything but thanks to a great design from [Kolibri] called klais-16. They’re available fully assembled if you want to jump straight to code, but thanks to thorough documentation (seriously, check this out) assembly is a snap.

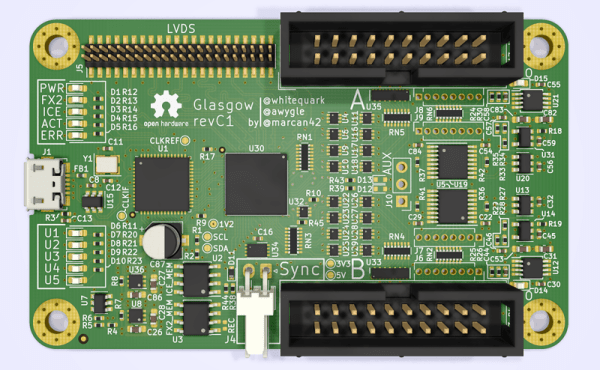

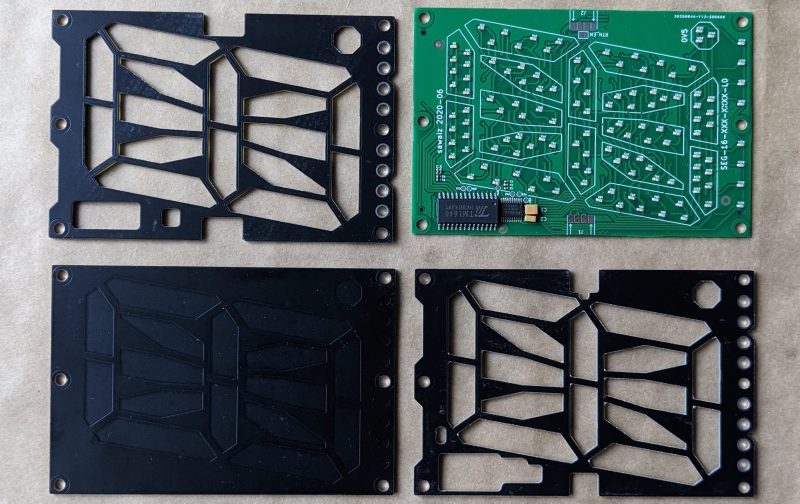

Each module is composed a very boring PCBA base layer which should be inexpensive from the usual sources, even when ordering one fully assembled. A stackup of three more PCBs are used for spacing and diffusion with plans for die-cut or injection mold layers if a larger production run ends up happening. Board dimensions for each character are 100 mm x 66.66 mm (about 4″ x 2.5″). Put together, each module can stand on its own or be easily daisy-chained together to make a longer single display.

Each module is composed a very boring PCBA base layer which should be inexpensive from the usual sources, even when ordering one fully assembled. A stackup of three more PCBs are used for spacing and diffusion with plans for die-cut or injection mold layers if a larger production run ends up happening. Board dimensions for each character are 100 mm x 66.66 mm (about 4″ x 2.5″). Put together, each module can stand on its own or be easily daisy-chained together to make a longer single display.

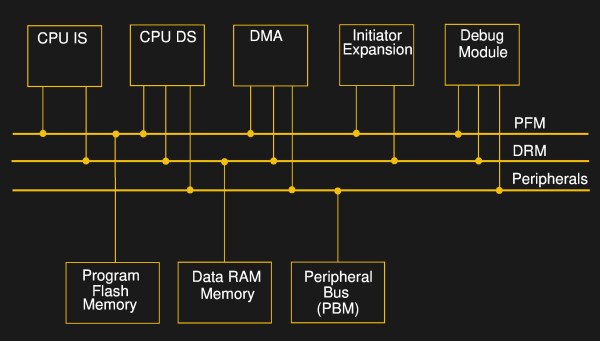

Addressing all those bits with an elaborate, ugly control scheme would be a drag but fortunately the firmware for the onboard STM8 microcontroller exposes a nice boring serial interface which can be used without configuration to display strings. There’s even an example Windows Batch script!