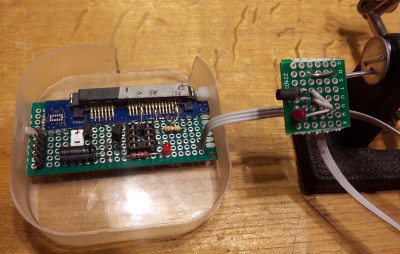

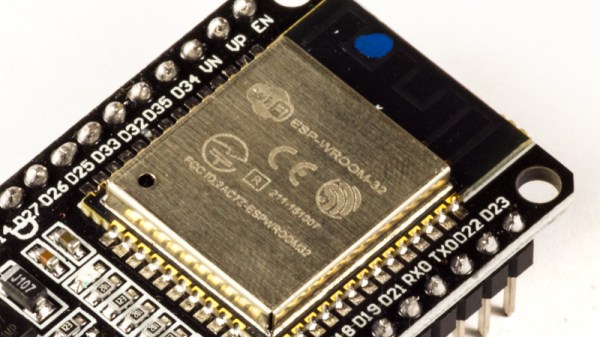

We’ve often said that one of the best applications for desktop 3D printing is the production of custom enclosures, but you certainly aren’t limited to an extruded version of the classic Radio Shack project box. As [Marcello Milone] shows with this very clever retro TV enclosure for the Wemos D1 Mini, 3D printing means your imagination is the only limit when it comes to how you want to package up your latest creation.

As nice as the printed parts are, it’s the little details that really sell the look. [Marcello] has bent a piece of copper wire into a circle to make a faux antenna with vintage flair, and while the ESP is connecting to the WiFi network, it even shows an old school TV test pattern on its 1.8″ TFT display.

As nice as the printed parts are, it’s the little details that really sell the look. [Marcello] has bent a piece of copper wire into a circle to make a faux antenna with vintage flair, and while the ESP is connecting to the WiFi network, it even shows an old school TV test pattern on its 1.8″ TFT display.

In the video after the break you can see the device go through its startup routine, and while displaying the Hackaday Wrencher at boot might not be strictly on theme…we’ll allow it.

While you could certainly use this little enclosure for whatever ESP project you had in mind, [Marcello] says he’s building a distributed environmental monitoring network using HTU21D temperature and humidity sensors. It sounds like he’s still working on the software side of things though, so hopefully he posts an update when the functionality is fully realized.

Continue reading “3D Printed ESP8266 TV Is A Blast From The Past”

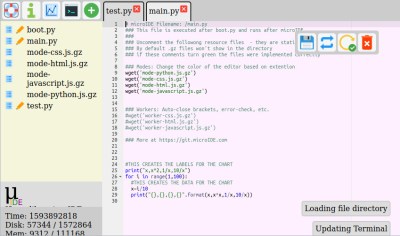

Using the IDE is easy enough, install a binary, connect to the ESP with a web browser, start writing MicroPython code. There is a choice of connecting directly to the chip as a hotspot, or connecting via another WiFi network. The interface is looking pretty slick but he’s at pains to remind us that it’s a work in progress. Sadly there is no source code yet as it’s a binary distribution that is free for non-commercial use, we’d hope that an open-source release might one day happen. It’s not for everyone, but the convenience of accessing the same interface from almost any modern device should help attract a healthy community.

Using the IDE is easy enough, install a binary, connect to the ESP with a web browser, start writing MicroPython code. There is a choice of connecting directly to the chip as a hotspot, or connecting via another WiFi network. The interface is looking pretty slick but he’s at pains to remind us that it’s a work in progress. Sadly there is no source code yet as it’s a binary distribution that is free for non-commercial use, we’d hope that an open-source release might one day happen. It’s not for everyone, but the convenience of accessing the same interface from almost any modern device should help attract a healthy community.