For his latest project, weather display aficionado [Richard] has put together a handsome little device that shows the temperatures recorded at nine different airports located all over the British Isles. Of course the concept could be adapted to wherever it is that you call home, assuming there are enough Internet-connected weather stations in the area to fill out the map.

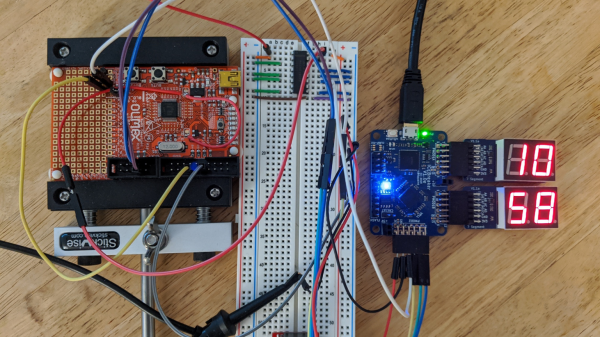

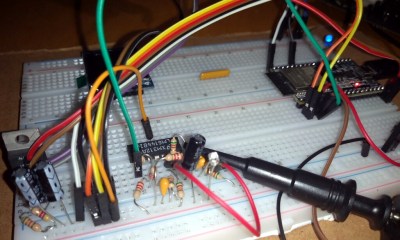

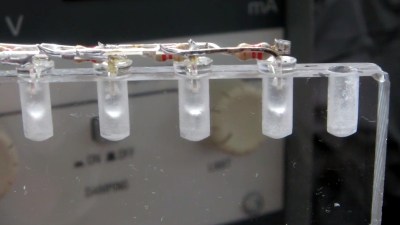

The electronics are fairly minimal, consisting of a NodeMCU ESP8266 development board, a few seven segment LED display modules, and a simple power supply knocked together on a scrap of perfboard. As you might expect, the code is rather straightforward as well. It just needs to pull down the temperatures from an online API and light up the displays. What makes this project special is the presentation.

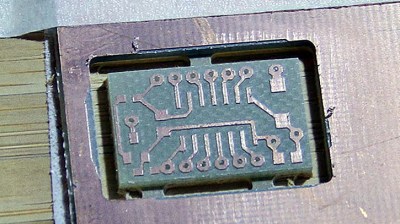

As [Richard] shows in the video after the break, the key is a sheet of acrylic that’s been sanded so it diffuses the light of 42 LEDs that have been painstakingly installed in holes drilled around the edge of the sheet. Combined with a printed overlay sheet, this illuminates the map and its legend in low-light conditions. It’s a simple technique that not only looks fantastic, but makes the display easy to read day or night. Definitely a tip worth mentally filing away, as it has plenty of possible applications outside of this particular build.

As [Richard] shows in the video after the break, the key is a sheet of acrylic that’s been sanded so it diffuses the light of 42 LEDs that have been painstakingly installed in holes drilled around the edge of the sheet. Combined with a printed overlay sheet, this illuminates the map and its legend in low-light conditions. It’s a simple technique that not only looks fantastic, but makes the display easy to read day or night. Definitely a tip worth mentally filing away, as it has plenty of possible applications outside of this particular build.

With his projects, [Richard] has shown himself to be a master of unique and data-rich weather displays, and a great lover of the iconic seven segment LED display. While his particular brand of climate data overload might not be for everyone, you’ve got to admire his knack for visualizing data.