There’s still plenty of useful hardware out there that uses an RS-232 interface, like the Behringer Ultradrive loudspeaker systems that [Lasse Lukkari] works with from time to time. Rather than ditch perfectly good gear because modern computers (to say nothing of phones or tablets) don’t have physical serial ports, he decided to come up with a WiFi adapter for these old devices that he calls SerialChiller.

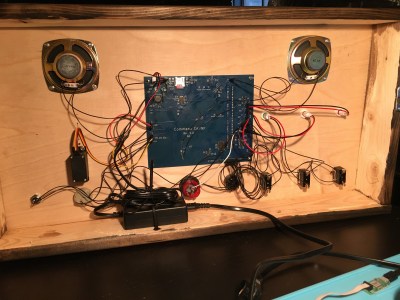

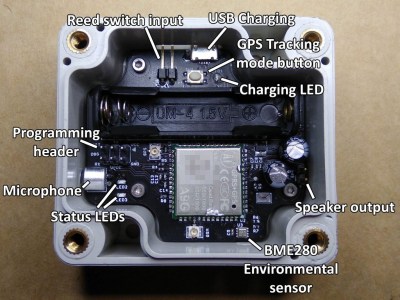

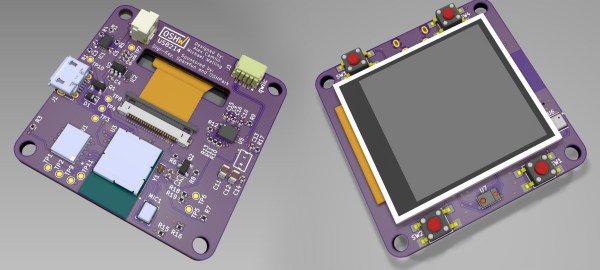

Inside the SerialChiller is an ESP32, a MAX3232 line driver, a LM1117 linear regulator, and a few passives. The professionally manufactured PCB is housed inside of an enclosure that [Lasse] has repurposed from a cheap DB15 breakout adapter. The USB cable is used to power the board and for programming, though it can also be used to turn the SerialChiller into a USB-to-serial cable as well.

The hardware for this project is pretty straightforward, but what we really like is the direction he’s taken with the software. Rather than using the SerialChiller as a simple serial to WiFi bridge, [Lasse] is actually implementing a complete web-based interface directly on the microcontroller. In the video after the break he demonstrates his firmware for controlling the aforementioned Behringer Ultradrive, but that’s just one possible application for the project. Firmware could be spun up for all sorts of classic devices, breathing new life into hardware that might otherwise be in danger of heading to the landfill.

Of course, using the ESP family of chips as serial adapters is hardly anything new. In fact, that’s what they were designed for. But developing modern user interfaces for old hardware thanks to the power of the ESP32 has some fascinating potential.

Continue reading “ESP32 Serial Interface Modernizes Old Equipment”