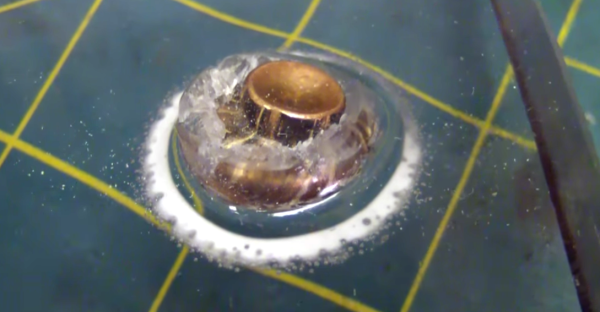

[thelostspore] was experimenting with resin casting, and discovered that he needed a pressure casting chamber in order to get clear casts. There are commercial solutions for sale, and they are really nice. However, many hackers are on a budget, and if you’re only casting every now and then you don’t need such a fancy set-up.

Re-purposing equipment like this is pretty common in the replica prop making community. Professional painters use a pressurized pot filled with paint to deliver to their spray guns. These pots can take 60-80 PSI and are built to live on a job site. By re-arranging some of the parts you can easily get a chamber that can hold 60 PSI for enough hours to successfully cast a part. Many import stores sell a cheap version, usually a bit smaller and with a sub-par gasket for around 80 US Dollars. [thelostspore] purchased one of these, removed the feed tube from lid and plugged the outlet. He then attached a quick release fitting to the inlet of the regulator.

We used this guide to build our own pressure casting set-up. Rather than plug up the outlet on ours, we put a ball valve with a muffler in its place to quickly and safely vent the chamber when the casting has set. We recommend putting a female quick connect coupling or another ball valve in combination with the male fitting (if your hose end is female). It is not super dangerous to do it the way the guide recommends, but this is safer, and you can disconnect the compressor from the tank without losing pressure.

All that was left was to test it. He poured an identical mold and it came out clear!

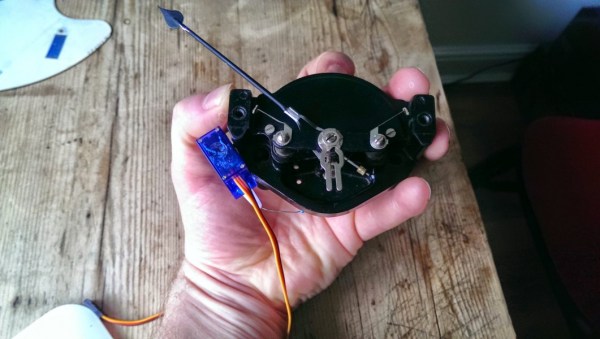

Being an aficionado of big engineering helped [mechanicalsquid] come up with a style for his gauge – big old dials and meters. We hesitate to apply the “steampunk” label to every project that retasks old technology, but it sure looks like a couple of the gauges he used could have been for steam, so the moniker probably fits here. Weather data for favorite kitesurfing and windsurfing locales is scraped from the web and applied to the gauges to indicates wind speed and direction. [mechanicalsquid] made a valiant effort to drive the voltmeter coil directly from the Raspberry Pi, but it was not to be. Servos proved inaccurate, so steppers do the job of moving the needles on both gauges. Check out the nicely detailed build log for this one, too.

Being an aficionado of big engineering helped [mechanicalsquid] come up with a style for his gauge – big old dials and meters. We hesitate to apply the “steampunk” label to every project that retasks old technology, but it sure looks like a couple of the gauges he used could have been for steam, so the moniker probably fits here. Weather data for favorite kitesurfing and windsurfing locales is scraped from the web and applied to the gauges to indicates wind speed and direction. [mechanicalsquid] made a valiant effort to drive the voltmeter coil directly from the Raspberry Pi, but it was not to be. Servos proved inaccurate, so steppers do the job of moving the needles on both gauges. Check out the nicely detailed build log for this one, too.