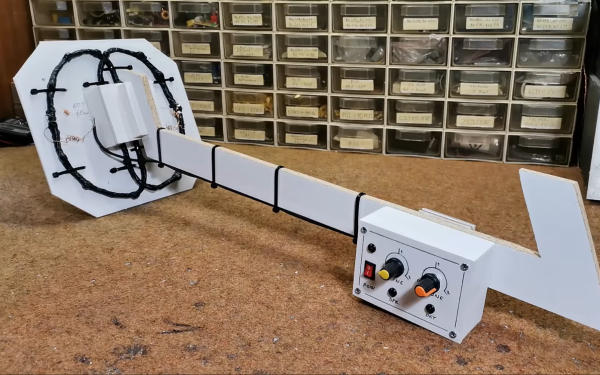

Steam turbines are at the heart of all manner of industrial machinery, particularly that used for power generation. [Integza] decided he needed to better understand this technology, and decided to build one himself – using 3D printing, at that.

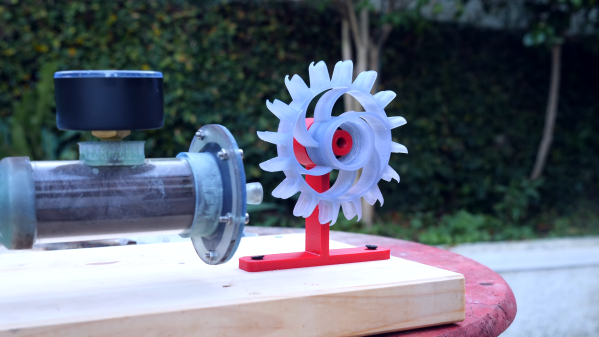

First, a steam source was needed, with a pressure cooker on an electric stove pressed into service. The steam was passed out via a nozzle printed in resin, which better resists heat than most FDM-printed parts. Similarly, a turbine wheel was printed in resin as well, with the steam outlet pointed directly at its vanes.

To really stress test the parts, more steam was required. To achieve this, hydrogen peroxide was pumped through a manganese dioxide catalyst impregnated into steel wool to create steam. This made an absolute mess, but the printed parts nevertheless survived.

The steam turbine didn’t do any useful work, but was able to survive the high temperatures at play. We’d love to see such a device actually used to bear some load, perhaps in some sort of 3D printed power generating turbine design.

Alternatively, if you prefer your steam turbines more classically driven, consider this build. Video after the break.