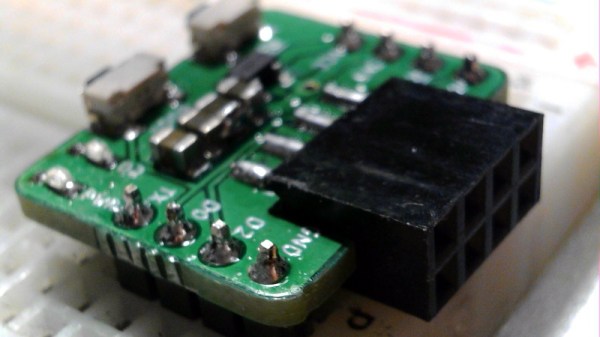

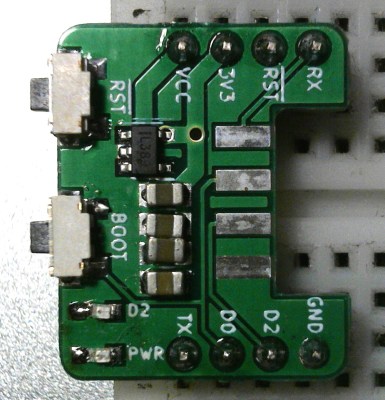

We’ve often said that one of the best applications of desktop 3D printing is the production of custom enclosures. A bespoke case adds a touch of professionalism to any project, and considering the materials needed to print one will cost less than even the cheapest generic project box, it’s a no-brainer. There’s only one problem: it can take hours to print even a simple case.

To try and speed things up, [Electrobob] has been experimenting with running off enclosures using spiral or “vase” mode on his 3D printer. Unlike the normal layer-by-layer approach, in this mode, the printer’s hotend continually rises at a steady rate during the entire print. Think of it as akin to printing out a Slinky and you should get the idea.

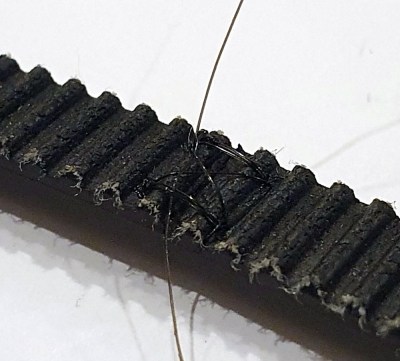

As you might expect, there are some trade-offs here. For one, the walls of the box can’t be very thick since the printer is only making one pass. The nozzle on most printers is 0.4 mm, but in his experiments, [Electrobob] has found he’s able to reliably double that to a wall thickness of 0.8 mm by adjusting the extrusion rate.

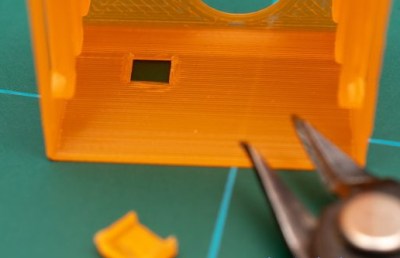

You also need to approach the design a bit differently during the CAD phase. Printing holes in the side of the enclosure, which would be easy enough to do normally, doesn’t really work when running in spiral mode. For those situations, [Electrobob] recommends designing a “pocket” into the side that you can come back and cut out with a knife. It will add a little time to the post-processing stage, but the time saved during the print will more than make up for it.

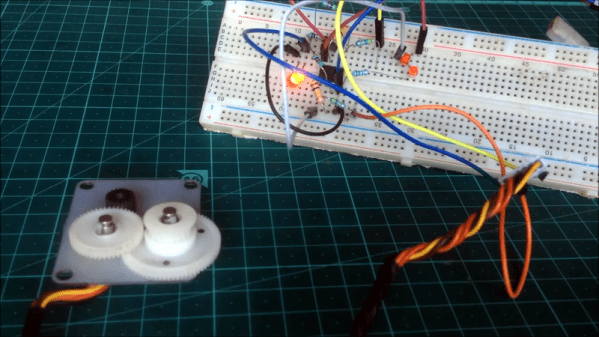

So how much faster are we talking about? In the example [Electrobob] shows in his write-up, the print time went from nearly two hours to just 18 minutes. The resulting enclosure obviously looks a bit different than the traditionally printed version, and isn’t as strong, but the concept still clearly holds promise for some applications. If you’re building a sensor network that needs a bunch of enclosures, those time savings will really add up.