Golf balls are wonderfully tactile things. They have a semi-grippy covering, and they’re a beautiful size and weight that sits nicely in the hand. Sadly, most of them just get smacked away with big metal clubs. [Jeremy Cook] recognized their value as a human interface device, though, and set about turning one into a useful volume knob.

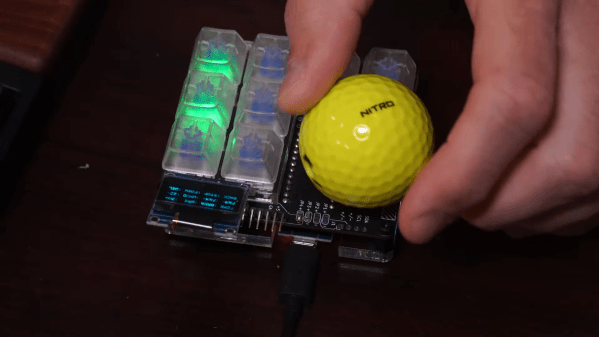

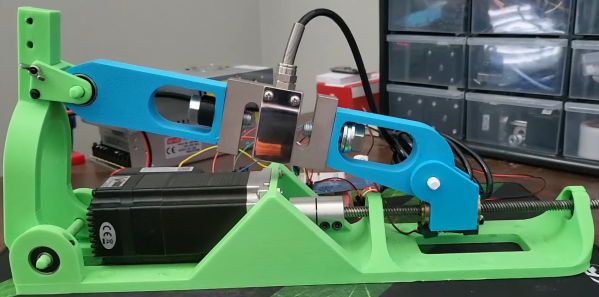

The trick here is in the machining. [Jeremy] used a 3D printed jig to hold a golf ball tightly in place so that it could be machined using a milling machine. With the bottom taken off and a carefully-designed 3D printed insert in the bottom, the golf ball is ready to be used as a knob for a volume control. As for the hardware side of things, [Jeremy] used an existing USB keypad, fitting the golf ball onto the encoder for volume and seek control in various programs.

The results sadly weren’t ideal. While the golf ball sits nicely upon the encoder, [Jeremy] found the device uncomfortable to use. Size may be an issue, but we also suspect the crowding of the surrounding buttons has a role to play. It forces the wrist into an uncomfortable curve to access the ball without hitting the surrounding controls. Without that, it may be greatly improved.

Files are available for those wishing to make their own. We don’t get a lot of golf ball builds here on Hackaday, but we’d love to see more. Hit up the tipsline if you’ve got ’em. Video after the break.

Continue reading “Machining A Golf Ball To Make A Lovely Tactile Volume Knob”