It’s easy to dismiss decades old electronics as effectively e-waste. With the rapid advancements and plummeting prices of modern technology, most old hardware is little more than a historical curiosity at this point. For example, why would anyone purchase something as esoteric as 1980-era video production equipment in 2018? A cheap burner phone could take better images, and if you’re looking to get video in your projects you’d be better off getting a webcam or a Raspberry Pi camera module.

But occasionally the old ways of doing things offer possibilities that modern methods don’t. This fascinating white paper from [David Prutchi] describes in intricate detail how a 1982 JVC KY-1900 professional video camera purchased for $50 on eBay was turned into a polarimetric imager. The end result isn’t perfect, but considering such a device would normally carry a ~$20,000 price tag, it’s good enough that anyone looking to explore the concept of polarized video should probably get ready to open eBay in a new tab.

But occasionally the old ways of doing things offer possibilities that modern methods don’t. This fascinating white paper from [David Prutchi] describes in intricate detail how a 1982 JVC KY-1900 professional video camera purchased for $50 on eBay was turned into a polarimetric imager. The end result isn’t perfect, but considering such a device would normally carry a ~$20,000 price tag, it’s good enough that anyone looking to explore the concept of polarized video should probably get ready to open eBay in a new tab.

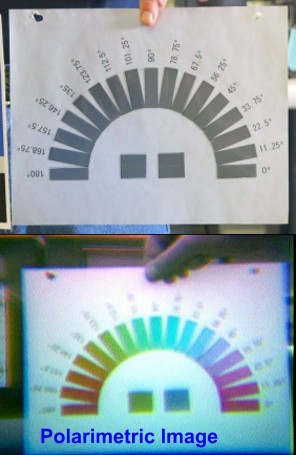

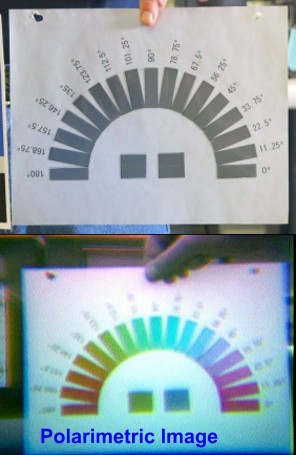

Likely many readers are not familiar with polarimetric imagers, it’s not exactly the kind of thing they carry at Best Buy. Put simply, it’s a device that allows the user to visualize the polarization of light in a given scene. [David] is interested in the technology as, among other things, it can be used to detect man-made materials against a natural backdrop; offering a potential method for detecting mines and other hidden explosives. He presented a fascinating talk on the subject at the 2015 Hackaday SuperConference, and DOLpi, his attempt at building a low-cost polarimetric imager with the Raspberry Pi, got him a fifth place win in that year’s Hackaday Prize.

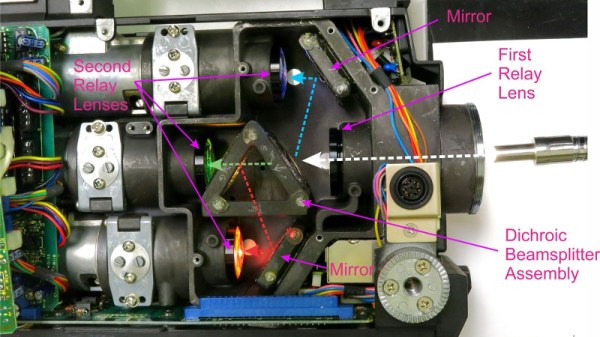

While he got good results with his Raspberry Pi solution, it took several seconds to generate a single frame of the image. To be practical, it needed to be much faster. [David] found his solution in an unlikely place, the design of 1980’s portable video cameras. These cameras made use of a dichroic beamsplitter to separate incoming light into red, blue, and green images; and in turn, each color image was fed into a dedicated sensor by way of mirrors. By replacing the beamsplitter assembly with a new 3D printed version that integrates polarization filters, each sensor now receives an image that corresponds to 0, 45, and 90 degrees polarization.

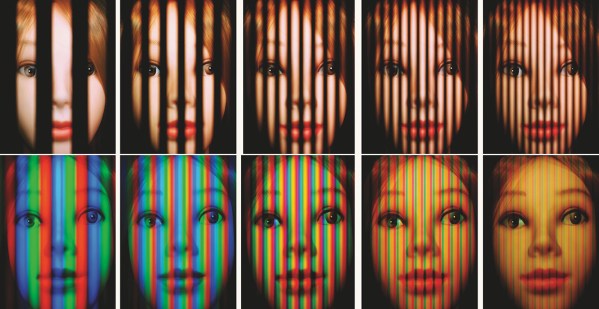

With the modification complete, the camera now generates real-time video that shows the angle of polarization as false color. [David] notes that the color reproduction and resolution is quite poor due to the nature of 30+ year old video technology, but that overall it’s a fair trade-off for running at 30 frames per second.

In another recent project, [David] found a way to hack optics onto a consumer-level thermal imaging camera. It’s becoming abundantly clear that he’s not a big fan of leaving hardware in an unmodified state.