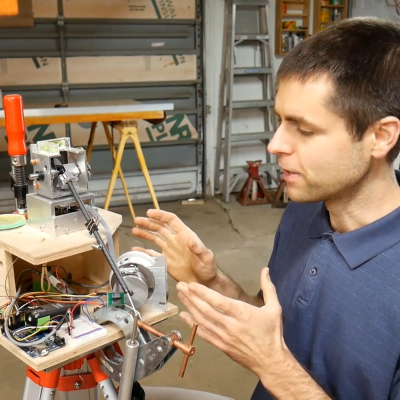

Last year, as my Corona Hobby™, I took up RC plane flying. I started out with discus-launched gliders, and honestly that’s still my main love, but there’s only so much room for hackery in planes that are designed to be absolutely minimum weight and maximum performance; these are the kind of planes that notice an extra half gram in the tail. So I’ve also built a few crude workhorse planes — the kind of things that you could slap a 60 g decade-old GoPro on and it won’t even really notice. Some have ended their lives in trees, but most have been disassembled and reincarnated — the electronics live on in the next body.

The journey has been really fun. I’ve learned about aerodynamics, gotten an excuse to put together a 4-axis hot-wire CNC styrofoam cutter, and covered everything in sight with carbon fiber tow, which is cheaper than you might think but makes the plane space-age. My current workhorse has bolted on an IMU, GPS, and a minimal Ardupilot setup, though I have yet to really put it through its paces. What’s holding me back is the video link — it just won’t work reliably further than a few hundred meters, and I certainly don’t trust it to get out of line-of-sight.

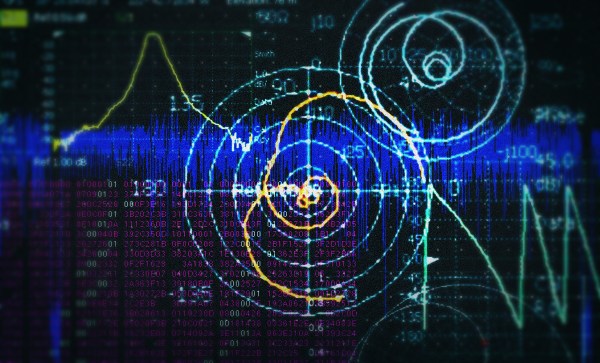

My suspicion is that the crappy antennas I have are holding me back, which of course is an encouragement to DIY, but measuring antennas in the 5.8 GHz band is tricky. I’d love to just be able to buy one of the cheap vector analyzers that we’ve covered in the past — anyone can make an antenna when they can see what they’re doing — but they top out at 2.4 GHz or lower. No dice. I’m blind in 5.8 GHz.

Of course, I do have one way in, and that’s tapping into the received signal strength indicator (RSSI) of a dedicated 5.8 GHz receiver, and just testing antennas out in practice, but that only gives a sort of loose better-worse indication. More capacitance or more inductance? Plates closer together or further apart? Try it out and see, I guess, but it’s time-consuming.

Moral of the story: don’t take measurement equipment for granted. Imagine trying to build an analog circuit without a voltmeter, or to debug something digital without a logic probe. Sometimes the most important tool is the one that lets you see the problem in the first place.