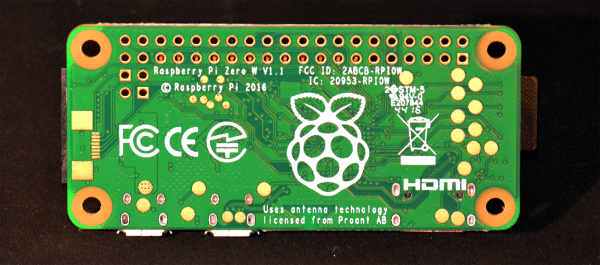

Putting a complete WiFi subsystems on a single-board computer is no mean feat, and on as compact a board as the Zero W, it’s quite an achievement. The antenna is the tricky part, since there’s only so much you can do with copper traces.

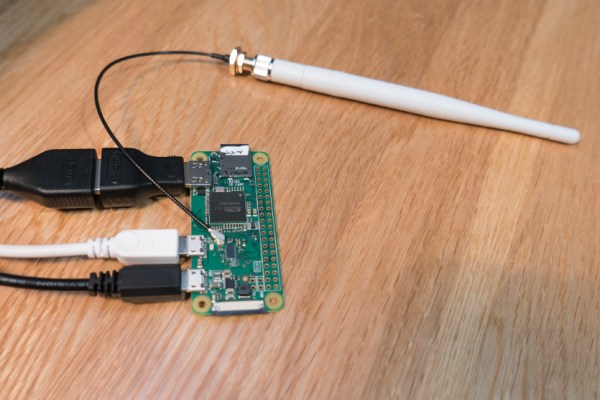

The new Raspberry Pi Zero W’s antenna is pretty innovative, but sometimes you need an external antenna to reach out and touch someone. Luckily, adding an external antenna to the Zero W isn’t that tough at all, as [Brian Dorey] shows us. The Pi Zero W’s designers thoughtfully included solder pads for an ultra-miniature surface-mount UHF jack. The jack pads are placed very close to the long, curving trace that acts as a feedline to the onboard antenna. There’s even a zero ohm SMT resistor that could be repositioned slightly to feed RF to the UHF jack. A little work with a soldering iron and [Brian]’s Pi was connected to an external antenna.

[Brian] includes test data, but aside from a few outliers, the external antenna doesn’t seem to offer a huge advantage, at least under his test conditions. This speaks to the innovative design of the antenna, which [Roger Thornton] from the Raspberry Pi Foundation discussed during last week’s last week’s Hack Chat. Check out the archive for that and more.

Thanks to [theEngineer] for the tip.