Digikey might wow us with their expansive stock, but now they’re wowing us with a personal gesture. The US-based electronics vendor is nodding its head in approval to KiCad users with its very own parts library. What’s more, [Chris Gammell] walks us through the main features and thought process behind its inception.

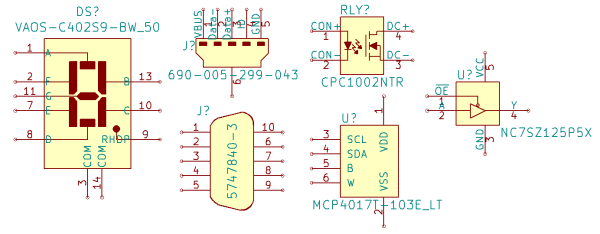

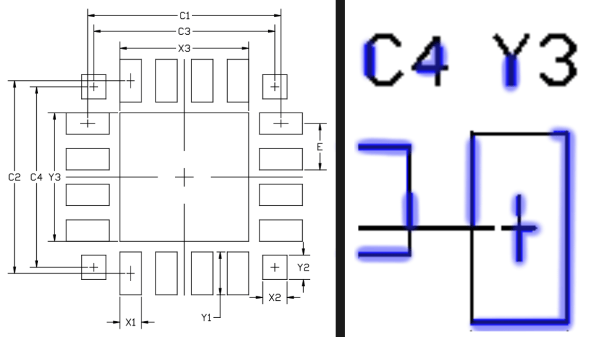

With all the work that’s going into this library, it’s nice to see features showing that Digikey took a thorough look at KiCad and how it fits into the current state of open-source PCBA design. First off, this library follows a slightly different design pattern from most other KiCad libraries in that it’s an atomic parts library. What that means is that every symbol is linked to a specific manufacturer part number and, hence, gets linked to a specific footprint. While this style mirrors EagleCad’s; KiCad libraries usually separate symbols from footprints so that symbols can be reused and parts can be more easily swapped in BOMs. There’s no “best” practice here, so the folks at Digikey thought they’d expose the second option.

Next off, the library is already almost 1000 parts strong and set to grow. These aren’t just the complete line of Yageo’s resistor inventory though. They actually started cultivating their library from the parts in Seeed Studio’s open parts library. These are components that hobbyists might actually use since some assembly services have a workflow that moves faster with designs that use these parts. Lastly, since all parts have specific vendor part numbers, BOM upload to an online cart is more convenient, making it slightly easier for Digikey to cha-ching us for parts.

Yes, naysayers might still cry “profit” or “capitalism” at the root of this new library, but from the effort that’s gone into this project, it’s a warm gesture from Digikey that hits plenty of positive personal notes for hobbyists. Finally, we can still benefit from plenty of the work that’s gone into this project — even if we don’t use it as intended. The permissive license lets us snag the symbols and reuse them however we like. (In fact, for the sharp-eyed legal specialists, they actually explicitly nullified the clause stating that derivative projects need not be licensed with a creative-commons license.)

With maturing community support from big vendors like Digikey, we’re even hungrier to get our hands on KiCad V.

Continue reading “Digikey Tips Its Hat To Kicad With Its Own Library”