When it rain, it pours. One of the primary support cables holding up the Arecibo Observatory dish in Puerto Rico has just snapped, leaving its already uncertain fate. It had been badly damaged by Hurricane Maria in 2017, and after a few years of fundraising, the repairs were just about to begin on fixing up that damage, when the cable broke. Because the remaining cables are now holding increased weight, humans aren’t allowed to work on the dome until the risk of catastrophic failure has been ruled out — they’re doing inspection by drone.

Arecibo Observatory has had quite a run. It started out life as part of a Cold War era ICBM-tracking radar, which explains why it can transmit as well as receive. And it was the largest transmitting dish the world had. It was used in SETI, provided the first clues of gravitational waves, and found the first repeating fast radio bursts. Its radar capabilities mean that it could be used in asteroid detection. There are a number of reasons, not the least of which its historic import, to keep it running.

So when we ran this story, many commenters, fearing the worst, wrote in with their condolences. But some wrote in with outrage at the possibility that it might not be repaired. The usual suspects popped up: failure to spend enough on science, or on infrastructure. From the sidelines, however, and probably until further structural studies are done, we have no idea how much a repair of Arecibo will cost. After that, we have to decide if it’s worth it.

So when we ran this story, many commenters, fearing the worst, wrote in with their condolences. But some wrote in with outrage at the possibility that it might not be repaired. The usual suspects popped up: failure to spend enough on science, or on infrastructure. From the sidelines, however, and probably until further structural studies are done, we have no idea how much a repair of Arecibo will cost. After that, we have to decide if it’s worth it.

Per a 2018 grant, the NSF was splitting the $20 M repair and maintenance bill with a consortium led by the University of Central Florida that will administer the site. With further damage, that might be an underestimate, but we don’t know how much of one yet.

When do you decide to pull the plug on something like this? Although the biggest, Arecibo isn’t the only transmitter out there. The next largest transmitters are part of Deep Space Network, though, and are busy keeping touch with spacecraft all around our solar system. For pure receiving, China’s FAST is bigger and better. And certainly, we’ve learned a lot about radio telescopes since Arecibo was designed.

I’m not saying that we won’t shed a tear if Arecibo doesn’t get repaired, but it’s not the case that the NSF’s budget has been hit dramatically, or that they’re unaware of the comparative value of various big-ticket astronomy projects. Without being in their shoes, and having read through the thousands of competing grant proposals, it’s hard to say that the money spent to prop up a 70 year old telescope wouldn’t be better spent on something else.

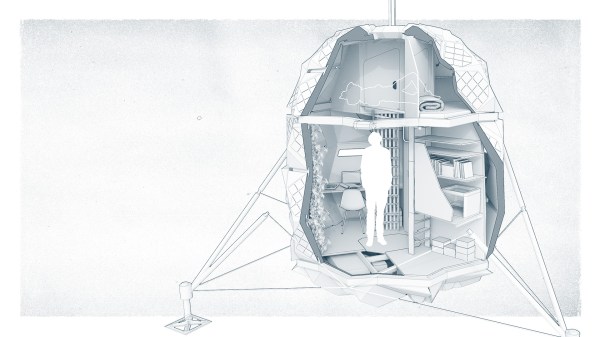

The habitat itself is a testament to the duo’s ingenuity. The whole structure folds to fit the tight space and weight requirements of rockets. Taking 2.9m3 (102 ft3) when stored, it expands 560% in volume to 17.2m3 (607 ft3). In Greenland, the structure needs to withstand -30ºC (-22ºF) and 90 km/h winds.

The habitat itself is a testament to the duo’s ingenuity. The whole structure folds to fit the tight space and weight requirements of rockets. Taking 2.9m3 (102 ft3) when stored, it expands 560% in volume to 17.2m3 (607 ft3). In Greenland, the structure needs to withstand -30ºC (-22ºF) and 90 km/h winds.