[Isabelle Simova] is building Hoverbot, a flexible robotics platform using Ikea plastic trays, JavaScript running on a Raspberry Pi and parts scavenged from commonly available hoverboards.

Self-balancing scooters a.k.a. Hoverboards are a great source of parts for such a project. Their high torque, direct drive brushless motors can drive loads of 100 kg or more. In addition, you also get a matching motor controller board, a rechargeable battery and its charging circuit. Most hoverboard controllers use the STM32F103, so flashing them with your own firmware becomes easy using a ST-link V2 programmer.

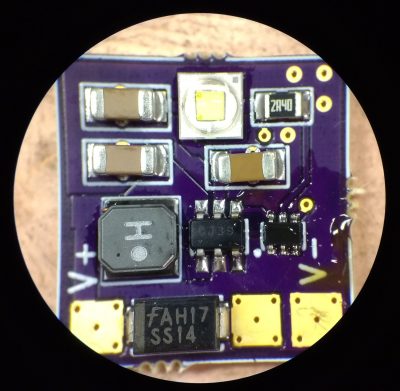

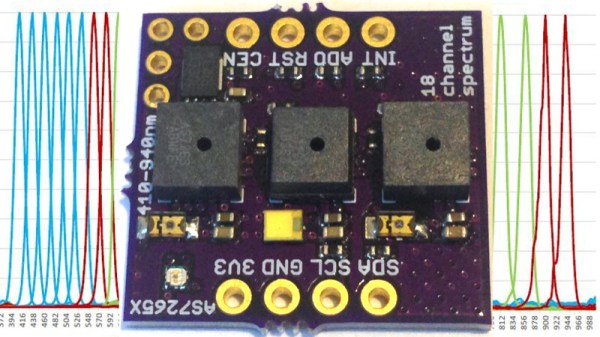

The next set of parts you need to build your robot is sensors. Some are cheap and easily available, such as microphones, contact switches or LDRs, while others such as ultrasonic distance sensors or LiDAR’s may cost a lot more. One source of cheap sensors are car parking assist transducers. An aftermarket parking sensor kit usually consists of four transducers, a control box, cables and display. Using a logic analyzer, [Isabelle] shows how you can poke around the output port of the control box to reverse engineer the data stream and decipher the sensor data. Once the data structure is decoded, you can then use some SPI bit-banging and voltage translation to interface it with the Raspberry Pi. Using the Pi makes it easy to add a cheap web camera, microphone and speakers to the Hoverbot.

Ikea is a hackers favourite, and offers a wide variety of hacker friendly devices and supplies. Their catalog offers a wide selection of fine, Swedish engineered products which can be used as enclosures for building robots. [Isabelle] zeroed in on a deep, circular plastic tray from a storage table set, stiffened with some plywood reinforcement. The tray offers ample space to mount the two motors, two castor wheels, battery and the rest of the electronics. Most of the original hardware from the hoverboard comes handy while putting it all together.

The software glue that holds all this together is JavaScript. The event-driven architecture of Node.js makes it a very suitable framework to use for Hoverbot. [Isabelle] has built a basic application allowing remote control of the robot. It includes a dashboard which shows live video and audio streams from the robot, buttons for movement control, an input box for converting text to speech, ultrasonic sensor visualization, LED lighting control, message log and status display for the motors. This makes the dashboard a useful debugging tool and a starting point for building more interesting applications. Check the build log for all the juicy details. Which other products from the Ikea catalog can be used to build the Hoverbot? How about a robotic Chair?

Continue reading “Turning That Old Hoverboard Into A Learning Platform” →