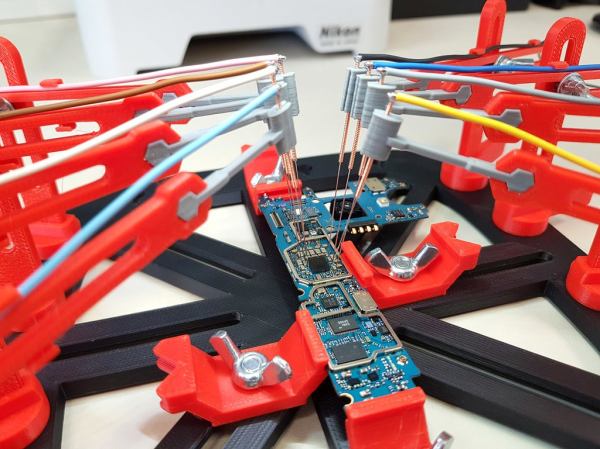

Trying to probe a modern electronic circuit with tiny SMD components, without letting the magic smoke escape in the process, can be quite a challenge. Especially since we hackers have not yet developed the number of appendages required to hold 3 different probes in place while operating both an oscilloscope and a computer. [Giuseppe Finizia] solved this problem with a 3D printed PCB probing jig that uses acupuncture needles.

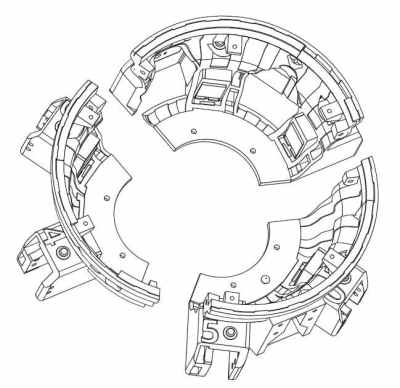

As part of [Giuseppe] day job as an engineer at an electronic forensics laboratory, he does technical investigations on seized devices, which involves quite a bit of probing. The jig consists of a base plate with slots in which PCB holders of various configurations slide to hold all shapes and sizes of PCBs. Around the circumference of the plate there are multiple positions for adjustable probing “cranes”, each of which hold an acupuncture needle that is crimped or soldered to a wire. Each needle holder has a bit of flex which allows it to maintain downward pressure for a positive connection.

Making one-off tools and jigs is arguably one of the best applications for 3D printing, of which this is a perfect example. You can of course point solder wires or use test hooks if you have something to grab onto, but for easily probing multiple point on any PCB, this looks like a damn good solution. If you’re trying to trace a single signal, a precision pantograph might be your friend, or you can add a foot switch to your oscilloscope for quickly checking a circuit by hand.

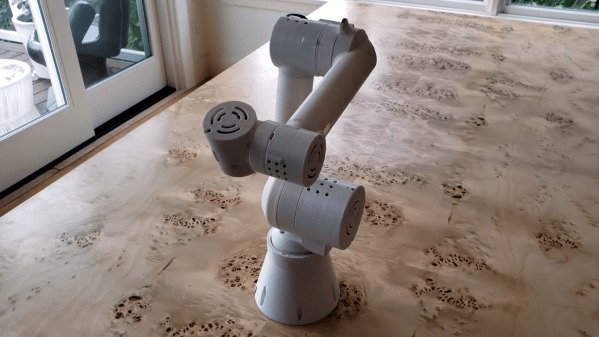

[Jonathon Oxer] from the YouTube channel SuperHouse did a very nice video on the jig and made some small modifications. Check out the video after the break.