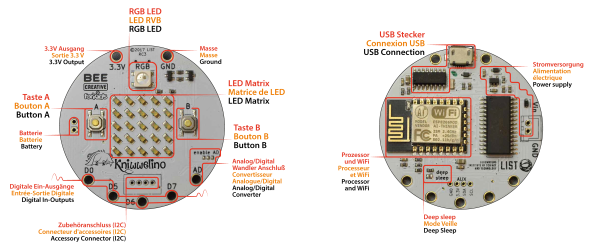

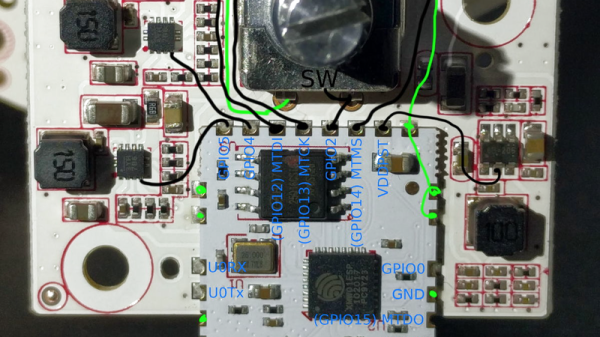

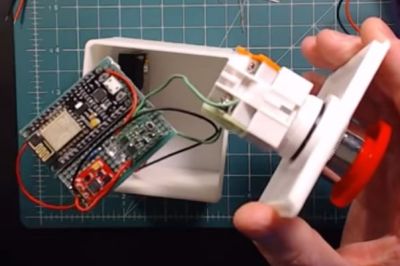

Kniwwelino is the latest in a line of micro:bit-inspired projects that we’ve seen, but this one comes with a twist: it uses an ESP8266 and WiFi at the core instead of the nR51 ARM/BTLE chip. That means that students can connect via laptop, cellphone, or anything else that can get onto a network.

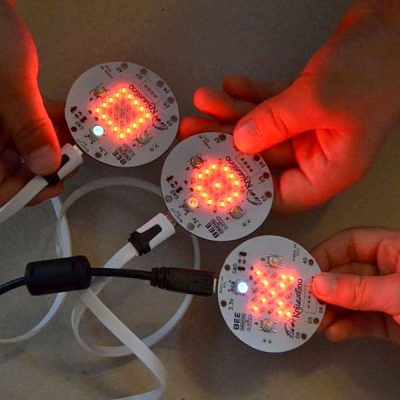

That’s not the only tradeoff, though. In order to get the price down, the Kniwwelino drops the accelerometer/magnetometer of the micro:bit for a programmable RGB LED. With fewer pins to break out, the Kniwwelino is able to ditch the love-it-or-hate-it card-edge connector of the micro:bit as well. In fact, with all these changes, it’s hard to call this a micro:bit clone at all — it’s more like a super-blinky ESP8266 development kit.

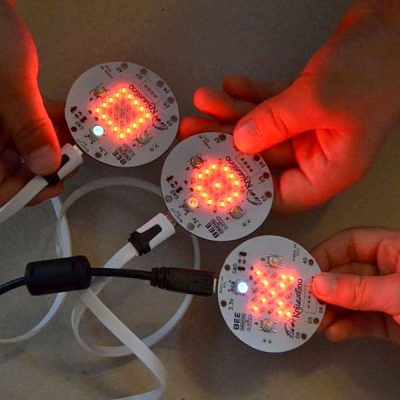

So what have they got left in common? The iconic 5×5 LED matrix in the center, and a Blockly visual programming dialect dedicated to the device. Based on the ESP8266, the Kniwwelino naturally also has an Arduino dialect that students can “graduate” to when they’re tired of moving around colored blobs, and of course you could flash the chip with anything else that runs on an ESP8266.

So what have they got left in common? The iconic 5×5 LED matrix in the center, and a Blockly visual programming dialect dedicated to the device. Based on the ESP8266, the Kniwwelino naturally also has an Arduino dialect that students can “graduate” to when they’re tired of moving around colored blobs, and of course you could flash the chip with anything else that runs on an ESP8266.

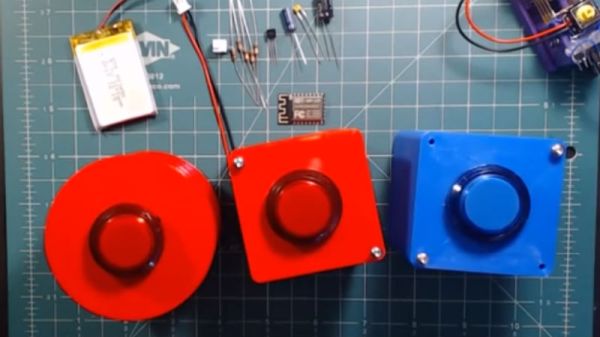

We don’t have one in our hands, but we like the idea. An RGB LED is a lot of fun on Day One, and the fact that the Kniwwelino fits so neatly into existing bodies of code makes the transition from novice to intermediate programmer a lot easier. These things are personal preference, but WiFi beats Bluetooth LE in our book, for sheer ubiquity and interoperability. Finally, the Kniwwelino comes in at about half the manufacturing cost of a micro:bit, which makes it viable in schools without large manufacturer subsidies. They’re estimating $5 per unit. (Retail is higher.) On the other hand, the Kniwwelino is going to use more juice than its ARM-based competitor, and doesn’t have an accelerometer.

Kniwwelino is apparently derived from a luxembourgish word “kniwweln” that apparently means to craft something. The German Calliope Mini is named after Zeus’ daughter, the programmer’s muse. We’re stoked to see so many cute dev boards getting into the hands of students, no matter what you call them.