Let’s say you’ve watched a few episodes of “The Joy of Painting” and you want your inner [Bob Ross] to break free. You get the requisite supplies for oil painting – don’t forget the alizarin crimson! – and start to apply paint to canvas, only to find your happy little trees are not so happy, and this whole painting thing is harder than it looks.

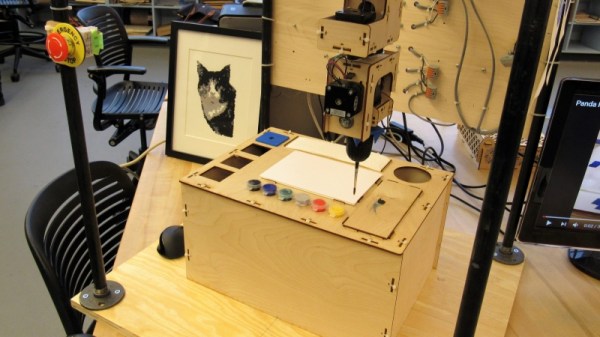

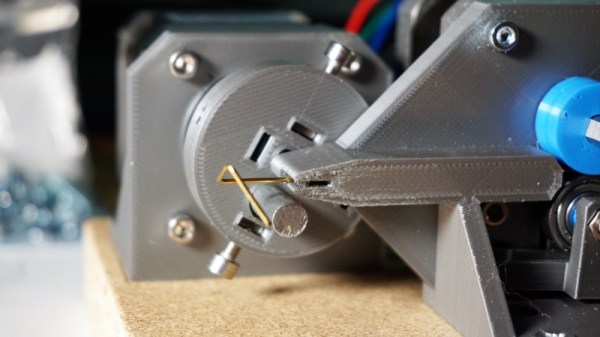

[Saint Bob] would certainly encourage you to stick with it, but if you have not the patience, a CNC painting robot might be a thing to build. The idea behind [John Opsahl]’s “If Then Paint” is not so much to be creative, but to replicate digital images in paint. Currently in the proof-of-concept phase, If Then Paint appears to have two main components: the paint management system, with syringe pumps to squeeze out different paints to achieve just the right color, and the applicator itself, a formidable six-axis device that supports tool changes by using different brushes chucked up into separate hand drill chucks. The extra axes at the head will allow control of how the brush is presented to the canvas, and also allow for cleaning the brush between colors. The videos below show two of the many ways [John] is exploring to clean the brushes, but sadly neither is as exciting as the correct [Bob Ross] method.

It looks like If Then Paint has a ways to go yet, but we’re impressed by some of the painting it has produced already. This is just the kind of project we like to see in the 2019 Hackaday Prize – thought out, great documentation, and a lot of fun.

Continue reading “Color Your World With This CNC Painting Robot”