Do you make things, and have you got almost ten minutes to spare? If not, make the time because this video by [PrintLab] is chock-full of healthy and practical design tips. It’s about effective design of Assistive Technology, but the design concepts extend far beyond that scope.

It’s about making things that are not just functional tools, but objects that are genuinely desirable and meaningful to people’s lives. There are going to be constraints, but constraints aren’t limits on creativity. Heck, some of the best devices are fantastic in their simplicity, like this magnetic spoon.

One item that is particularly applicable in our community is something our own [Jenny List] has talked about: don’t fall into the engineer-saviour trap. The video makes a similar point in that it’s easy and natural to jump straight into your own ideas, but it’s critical not to make assumptions. What works in one’s head may not work in someone’s actual life. The best solutions start with a solid and thorough understanding of an issue, the constraints, and details of people’s real lives.

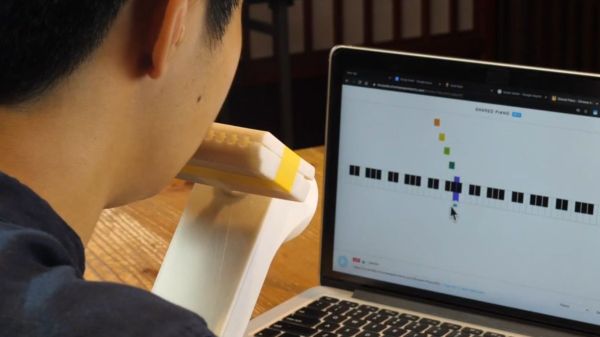

Another very good point is that designs don’t spring fully-formed from a workbench, so prototype freely using cardboard, models, 3D printing, or whatever else makes sense to you. Don’t be stingy with your prototyping! As long as you’re learning something each time, you’re on the right path.

And when a design is complete? It has the potential to help others, so share it! But sharing and opening your design isn’t just about putting the files online. It’s also about making it as easy as possible for others to recreate, integrate, or modify your work for their own needs. This may mean making clear documentation or guides, optimizing your design for ease of editing, and sharing the rationale behind your design choices to help others can build on your work effectively.

The whole video is excellent, and it’s embedded here just under the page break. Does designing assistive technology appeal to you? If so, then you may be interested in the Make:able challenge which challenges people to design and make a 3D printable product (or prototype) that improves the day-to-day life of someone with a disability, or the elderly. Be bold! You might truly help someone’s life.

Continue reading “Solid Tips For Designing Assistive Technology (Or Anything Else, Really)”