We’ve seen many DIY headphones projects on these fair pages over the years, but not many that are quite as DIY as the Ploopy Headphones. What makes this project interesting is the sheer depth of the construction, with every single part being made from what we might call base materials. Materials such as 3D printer filament, foam and felt, and the usual metallic vitamins.

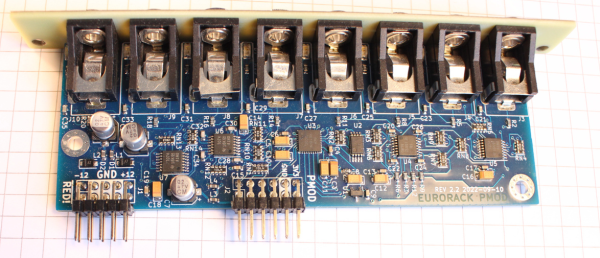

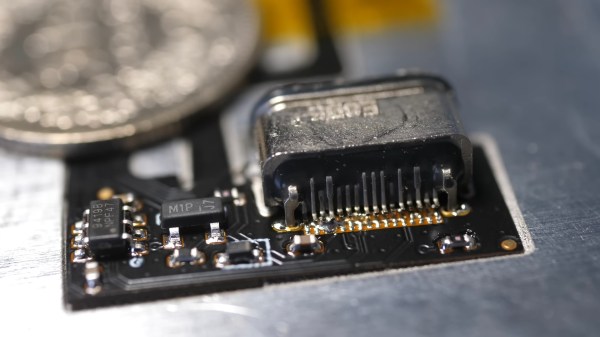

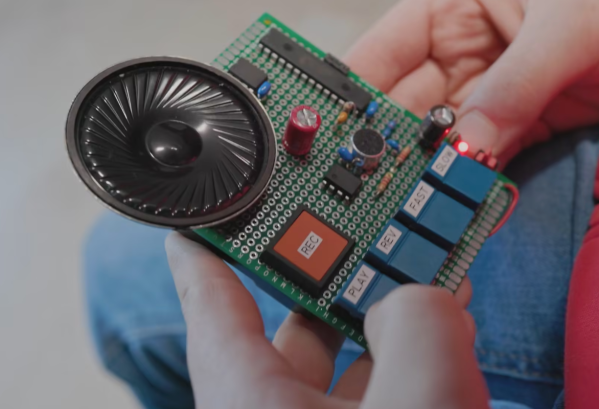

The electronics are fairly straightforward, with an RP2040 functioning as the USB audio interface and equalizer function. Audio samples are emitted as I2S into a PCM3050 24-bit stereo codec which generates a pair of differential output audio signals. These are then converted from differential to single-ended signals and passed on to the coil drivers. The coil drivers consist of no fewer than eight-paralleled opamps per channel. All of this is powered by the USB-C connection to the host computer. Whilst a kit of parts is available for this, you can make your own if you wish, as the full source (Altium designer needed for tweaks) is available on the Ploopy headphone GitHub.

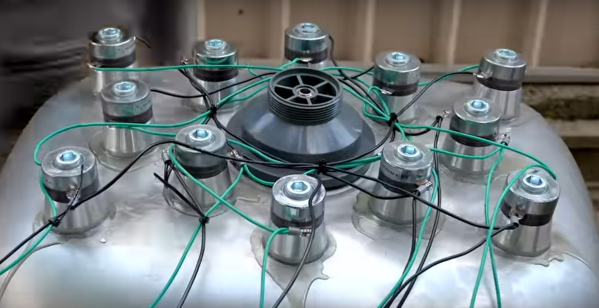

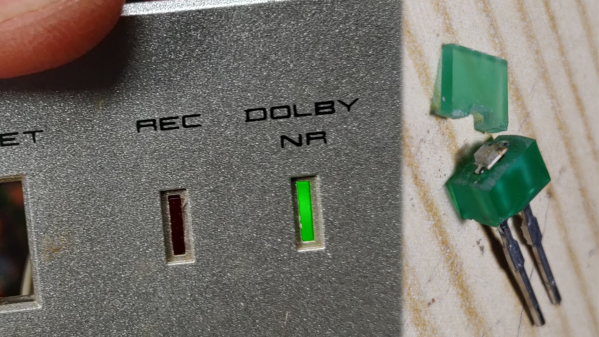

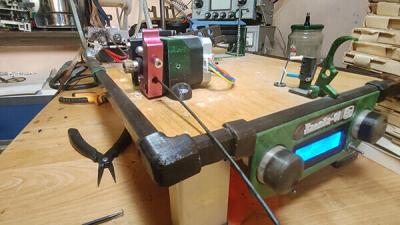

Many DIY headphone builds would likely be using off-the-shelf speaker units, with large parts of the ear cups being taken from spare parts kits for commercial offerings. But not the Ploopy. The drivers are constructed from flex PCB coils with a standard TRRS jack on each side. Magnets for these coils to react against are held in a 3D-printed frame that is attached to the outer cover. The coils are aligned with a special jig and bonded to the ‘driver foam’ with some 3M VHB tape.

The ear cups are constructed with some 3D printed rings, foam pieces, and simple woven material. The resonator plates push into the inner side of the cup, and the assembly simply screws to the driver assembly. The incredibly detailed assembly wiki makes it look easy, but we reckon there are a few tricky steps in there to trip the unwary. The headband again consists of printed spring sections, some woven material, and foam with a few metallic vitamins thrown in. That makes it sounds simple, but it isn’t.

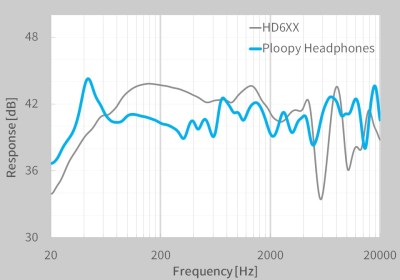

On the whole the build looks fantastic, but what does it sound like? The Ploopy team has tested them against a pair of Sennheiser HDRXX giving a broadly comparable response, but we’re no audio experts, and the proof, as always, is in the wearing. This project seems to be the ultimate in audio tweakability, with the punchy RP2040 capable of running six audio filters at the full 48 KHz, 16-bit audio, though, the PCM3050 is capable of more.

Want to build some headphones, but need a Bluetooth interface? We got you covered. Can 3D printed headphones ever compare to the big names? We’ll see.