Many moons ago, [Joe Grand] built an adapter that turns Atari 2600 joysticks to USB controllers. Now it’s open source.

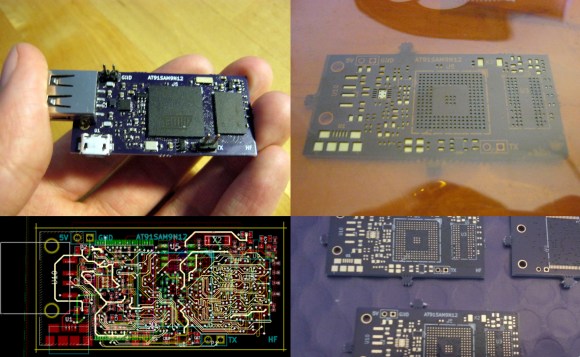

Hackaday Overlord [Matt] is holding an SMT and BGA soldering workshop in San Francisco on October 4th. Teaching BGA soldering? Yes! He made a board where the BGA balls are connected to LEDs. Very, very clever.

Our ‘ol friend [Jeremey Cook] built a strandbeest out of MDF. It’s huge, heavy, about the size of a small car, and it doesn’t work. [Jeremy] has built beests before, but these were relatively small. The big MDF beest is having some problems with friction, and a tendency to shear along the joints. If anyone wants to fix this beest, give [Jeremy] a ring.

Everyone loves the Teensy, and [Paul] has released his latest design iteration. The Teensy 3.2 isn’t that much different from the Teensy 3.1; the bootloader has changed and now USB D+ and D- lines are broken out. Other than that, it’s just the latest iteration of the popular Teensy platform.

The DyIO is a pretty neat robotics controller, a semifinalist for the Hackaday Prize, and now a Kickstarter. The big win of the Kickstarter is an electronics board (with WiFi) that is able to control 24 servos for all your robotics needs.

[pighixxx] does illustrations of pinouts for popular electronics platforms. Everyone needs a hobby, I guess. He recently put together an illustration of the ESP8266. Neat stuff is hidden deep in this site.

You would not believe how much engineering goes into making snake oil. And then you need to do certifications!

[David] identified a problem, created a solution, got a patent, and is now manufacturing a product. The only problem is the name.