Can you play chess against your printer? The answer will soon be yes, and it’s thanks to [Nicolas Seriot]’s PSChess. It’s a chess engine implemented in PostScript, of all things. It’s entirely working except for one last hurdle, but more on that in a moment.

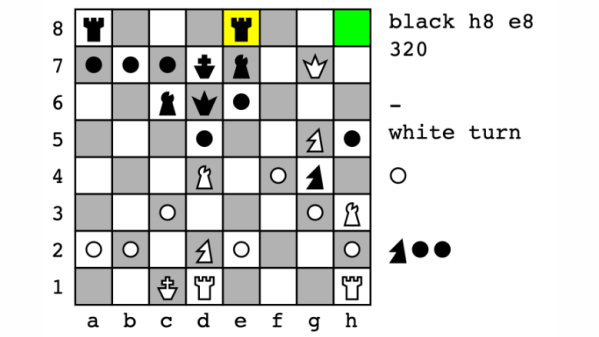

What’s it like to play PSChess? Currently, one uses a PostScript interpreter (such as GhostScript) to run it, much like one would use the Python interpreter to run Python code. The user inputs moves by typing in commands like d2d4 (representing a piece’s source coordinate and a destination coordinate on the 2D board). Then the program makes a move, and outputs an updated board state to both the console and a PDF document. Then it’s the user’s turn again, and so on until somebody loses.

The chess parts are all working, but there’s one last feature in progress. The final step of the project is to enable PSChess to be run directly on a printer instead of using GhostScript as the interpreter. Intrigued? You can find the code at the project’s GitHub repository.

So why PostScript? While it is a Turing-complete stack-based interpreted language, it was never intended to be used directly by humans. There are no meaningful development tools to speak of. Nevertheless, [Nicolas] finds PostScript an appealing tool for programming projects and provides tips and techniques for like-minded folks. One of the appeals is working within constraints to solve a problem, just like implementing a chess engine in only 4k, or draw poker in 10 lines of BASIC.