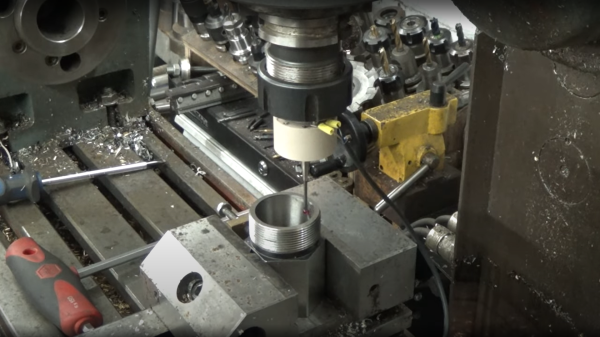

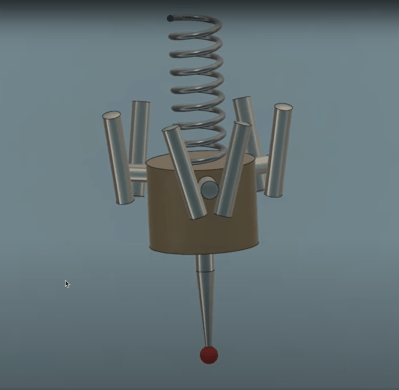

When you spend a lot of time on the computer doing certain more specialised tasks (no, we’re not talking about browsing cat memes on twitter) you start to think that your basic trackpad or mouse is, let’s say, lacking a certain something. We think that something may be called ‘usability’ or maybe ease-of-use? Any which way, lots of heavy CAD users gush over their favourite mouse stand-ins, and one particularly interesting class of input devices is the Space Mouse, which is essentially patented up-to-the-hilt and available only from 3DConnexion. But what about open source alternatives you can build yourselves? Enter stage left, the Orbion created by [FaqT0tum.] This simple little build combines an analog joystick with a rotary knob, with a rear button and OLED display on the front completing the user interface.

The idea is pretty straightforward; you setup the firmware with the application you want to use it with, and it emits HID events to the connected PC, replacing the mouse or keyboard input. Since your machine will take input from multiple sources, it doesn’t replace your mouse, it augments it. It may not be very accurate for detailed PCB layout work, but for moving around in a 3D view, or dialling in a video edit, this could be a very useful addition to your workstation, so why not give it a try? The wiring is simple, the parts easily found and cheap, and it’s only a few printed parts! This scribe is already printing the plastics right now, if you listen carefully you might be able to make out the sound of the Lulzbot in background.

There are many other takes on this idea, with varying levels of complexity, like this incredible build from [Ahmsville] that sadly doesn’t make the PCBs available openly, and here’s one we covered earlier mashing the expensive 3DConnexion spacemouse into a keeb.