JB Weld is a particularly popular brand of epoxy, and features in many legends. “My cousin’s neighbour’s dog trainer’s grandpa once repaired a Sherman tank barrel in France with that stuff!” they’ll say. Thankfully, with the advent of new media, there’s a wealth of content out there of people putting these wild and interesting claims to the test. As the venerable Grace Hopper once said, “One accurate measurement is worth a thousand expert opinions“, so it’s great to see these experiments happening.

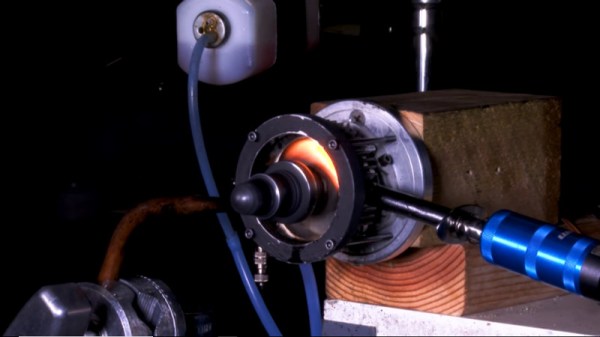

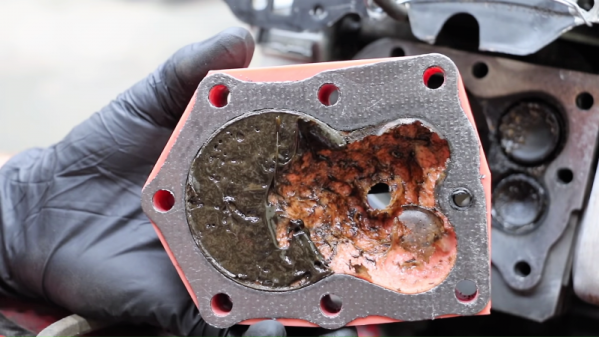

[Project Farm] is one of them, this time attempting to repair a connecting rod in a small engine with the sticky stuff. The connecting rod under test is from a typical Briggs and Stratton engine, and is very much the worse for wear, having broken into approximately 5 pieces. First, the pieces are cleaned with a solvent and allowed to properly dry, before they’re reassembled piece by piece with lashings of two-part epoxy. Proper technique is used, with the epoxy being given plenty of time to cure.

The result? Sadly, poor — the rod disintegrates in mere seconds, completely unable to hold together despite the JB Weld’s best efforts. It’s a fantastic material, yes – but it can’t do everything. Perhaps it could be used to cast a cylinder head instead?

Continue reading “JB Weld – Strong Enough To Repair A Connecting Rod?”

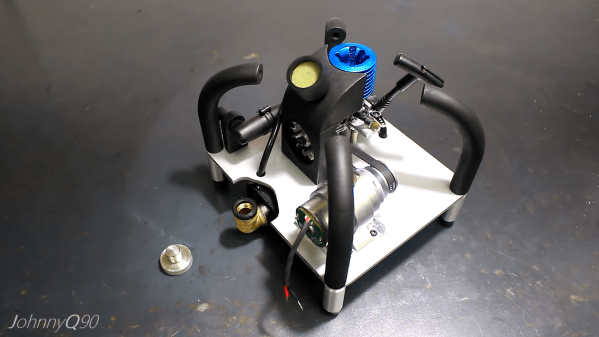

[JohnnyQ90] is, of course, no stranger to the nitro engine, having previously brought us the

[JohnnyQ90] is, of course, no stranger to the nitro engine, having previously brought us the

![A 1930s Morris Ten Series II. Humber79 [CC BY-SA 3.0].](https://hackaday.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/morris10080809e.jpg?w=400)