While ARM continues to make inroads into the personal computing market against traditional chip makers like Intel and AMD, it’s not a perfect architecture and does have some disadvantages. While it’s a great step on the road to software and hardware freedom, it’s not completely free as it requires a license to build. There is one completely open-source and free architecture though, known as RISC-V, and its design and philosophy allow anyone to build and experiment with it, like this build which implements a RISC-V processor in VHDL.

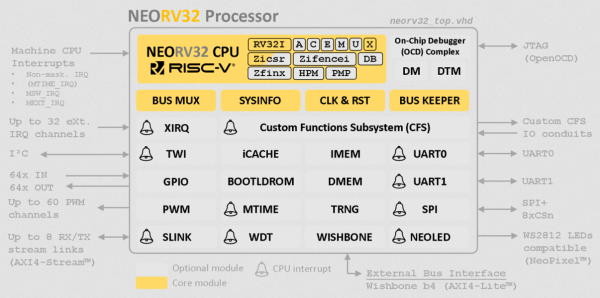

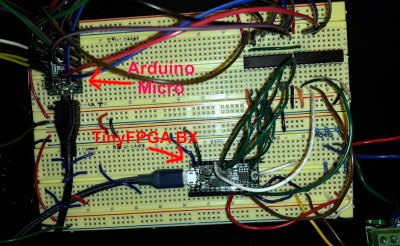

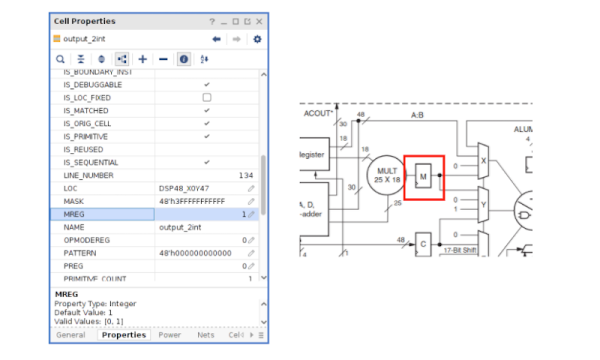

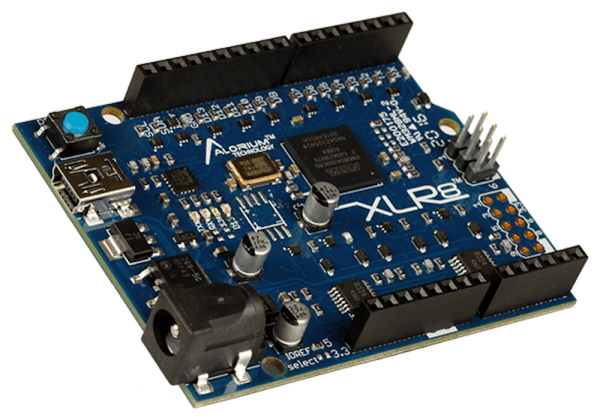

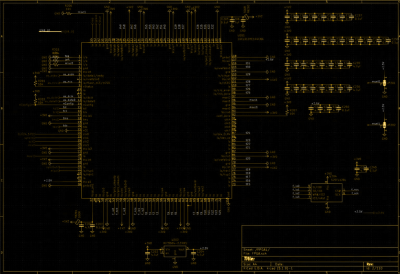

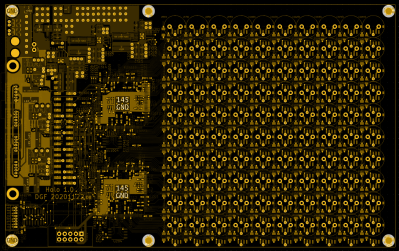

Since the processor is built in VHDL, a language which allows the design and simulation of integrated circuits, it is possible to download the code for the processor and then program it into virtually any FPGA. The processor itself, called NEORV32, is designed as a system-on-chip complete with GPIO capabilities and of course the full RISC-V processor implementation. The project’s creator, [Stephan], also struggled when first learning about RISC-V so he went to great lengths to make sure that this project is fully documented, easy to set up, and that it would work out-of-the-box.

Of course, since it’s completely open-source and requires no pesky licensing agreements like an ARM platform might, it is capable of being easily modified or augmented in any way that one might need. All of the code and documentation is available on the project’s GitHub page. This is the real benefit of fully open-source hardware (or software) which we can all get behind, even if there are still limited options available for RISC-V personal computers for the time being.

How does this compare to VexRISC or PicoSOC? We don’t know yet, but we’re always psyched to have choices.