Remember the Great Toilet Paper Crisis of 2020? We sure do, and it looks like our old friend [Vije Miller] does as well, while seemingly harboring a somewhat morbid fascination about how much paper every bathroom visitor is consuming. And to that end, we present his IoT toilet sheet tracker.

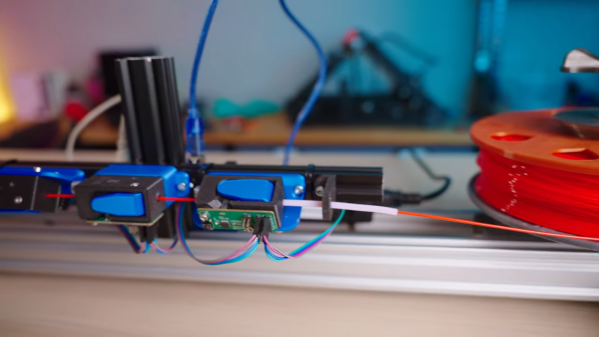

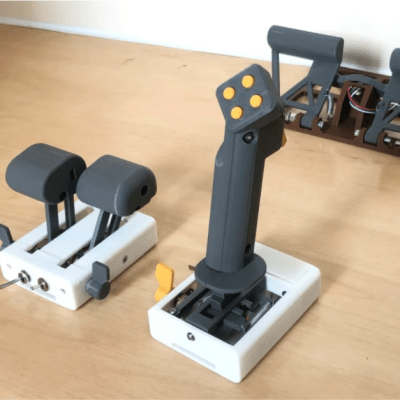

His 3D printed roll holder has a Hall effect sensor that counts revolutions of the roll and sends it to a NodeMCU. The number of sheets per roll is entered when the roll is changed, so some simple math yields the number of sheets each yank consumes. Or at least a decent estimate — [Vije] admits that there’s some rounding necessary. The best part of the build is the connection to Thingspeak, where sheet usage is plotted and displayed. Go ahead and check it out if you dare; at the time of writing, there was an alarming spike in sheet usage — a sudden need for 68 sheets where the baseline usage is in single digits. We shudder to think what might have precipitated that. The video below is — well, let’s just say there’s a video.

This isn’t the first time we’ve seen bathroom-based projects from [Vije Miller]. A few years back there was an attempt to freshen the air with plasma, and his IoT shower valve controller probably never scalded anyone accidentally.

Continue reading “Keep Track Of Toilet Paper Usage With This IoT Roll Holder”