Turning on a lightbulb has never been easier. You can do it from your mobile. Voice activation through home assistants is robust. Wall switches even play nicely with the above methods. It was only a matter of time before someone decided to make it fun, if you consider a Rubik’s cube enjoyable. [Alastair Aitchison] at Playful Technology demonstrated that it is possible to trigger a relay when you match all the colors. Video also after the break.

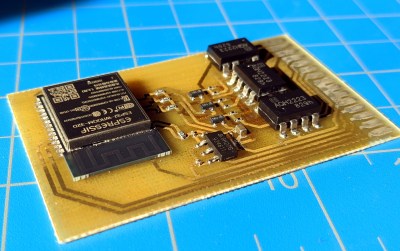

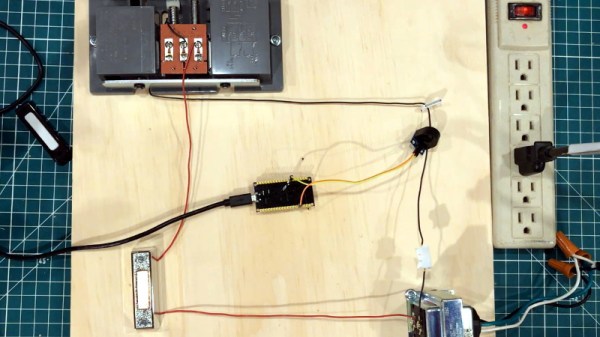

The cube does little to obfuscate game data, so in this scope, it sends unencrypted transmissions. An ESP32 with [Alastair]’s Arduino code, can track each movement, and recognize a solved state. In the video, he solves the puzzle, and an actuator releases a balloon. He talks about some other cool things this could do, like home automation or a puzzle room, which is in his wheelhouse judging by the rest of his YouTube channel.

We would love to see different actions perform remote tasks. Twisting the top could set a timer for 1-2-3-4-5 minutes, while the bottom would change the bedroom lights from red-orange-yellow-green-blue-violet. Solving the puzzle should result in a barrage of NERF darts or maybe keep housemates from cranking the A/C on a whim.