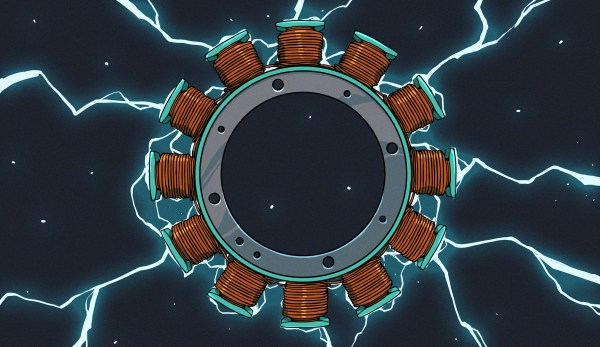

Perhaps the biggest hurdle to starting a home blacksmithing operating is the forge. There’s really no way around having a forge; somehow the metal has to get hot enough to work. Although we might be imagining huge charcoal- or gas-fired monstrosities, [Shake the Future] has figured out how to use an unmodified, standard microwave oven to get iron hot enough to melt and is using it in his latest video to cast real, working tools with it. (Also available to view on Reddit)

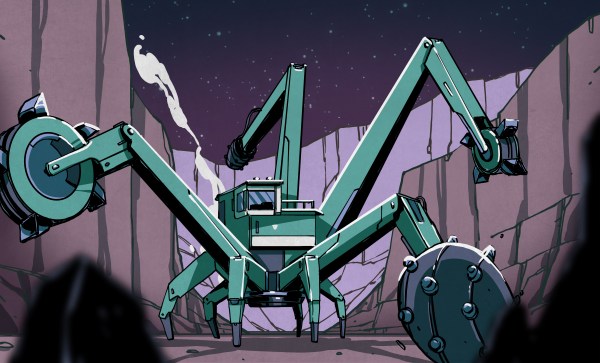

In the past, [Shake the Future] has made a few other things with this setup like an aluminum pencil with a graphite core. This time, though, he’s stepping up the complexity a bit with a working tool. He’s decided to build a miniature bench vice, which uses a screw to move the jaws. He didn’t cast the screw, instead using a standard size screw and nut, but did cast the two other parts of the vice. He first 3D prints the parts in order to make a mold that will withstand the high temperatures of the molten metal. With the mold made he can heat up the iron in the microwave and then pour it, and then with some finish work he has a working tool on his hands.

A microwave isn’t the only kitchen appliance [Shake the Future] has repurposed for his small metalworking shop. He also uses a standard air fryer in order to dry parts quickly. He works almost entirely from the balcony of his apartment so he needs to keep his neighbors in mind while working, and occasionally goes to a nearby parking garage when he has to do something noisy. It’s impressive to see what can be built in such a small space, though. For some of his other work be sure to check out how he makes the crucibles meant for his microwave.

Continue reading “Casting Metal Tools With Kitchen Appliances”