Anyone who has done anything with RGB LEDs knows that their ability to display pretty much any color is somehow both the best and worst thing about them. How do you get it right? How do you make your results repeatable? [Thomas] has the answer. He dug around in the ol’ parts cupboard, found a few pots, and got to work making this stay-home stew of a project — an on-demand RGB LED color mixer.

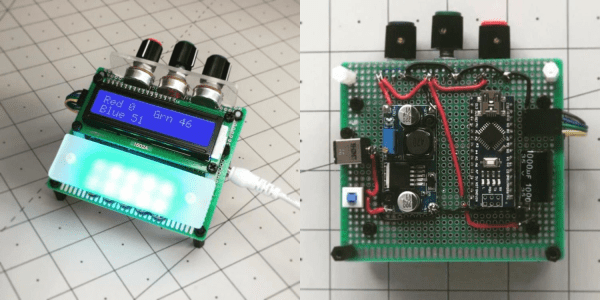

Three cleverly color-coded potentiometers and an Arduino let [Thomas] step through 0-255 to mix various values of red, blue, and green. The shade that gets made is displayed live on a set of 10 individual NeoPixels that are laid out under a frosty diffusing panel. Each of the RGB values are also shown on an 16×2 LCD.

This is one of those projects that hits a sweet spot of being simple, useful, and fun. It’s even nice-looking and compact. What more could you want from a project cobbled together from ingredients on hand? [Thomas] is even giving away the code recipe.

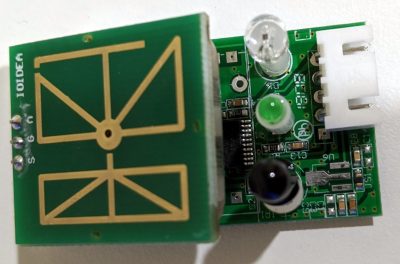

Once you dial in your ideal colors, why not make a gesture-controlled lamp?