We don’t have to tell you that drones are all the rage. But while new commercial models are being released all the time, and new parts get released for the makers, the basic technology used in the hardware hasn’t changed in the last few years. Sure, we’ve added more sensors, increased computing power, and improved the efficiency, but the key developments come in the software: you only have to look at the latest models on the market, or the frequency of Git commits to Betaflight, Butterflight, Cleanflight, etc.

With this in mind, for a Hackaday prize entry [int-smart] is working on a quadcopter testbed for developing algorithms, specifically localization and mapping. The aim of the project is to eventually make it as easy as possible to get off the ground and start writing code, as well as to integrate mapping algorithms with Ardupilot through ROS.

The initial idea was to use a Beaglebone Blue and some cheap hobby hardware which is fairly standard for a drone of this size: 1250 kv motors and SimonK ESCs, mounted on an f450 flame wheel style frame. However, it looks like an off-the-shelf solution might be even simpler if it can be made to work with ROS. A Scanse Sweep LIDAR sensor provides point cloud data, which is then munched with some Iterative Closest Point (ICP) processing. If you like math then it’s definitely worth reading the project logs, as some of the algorithms are explained there.

It might be fun to add FPV to this system to see how the mapping algorithms are performing from the perspective of the drone. And just because it’s awesome. FPV is also a fertile area for hacking: we particularly love this FPV tracker which rotates itself to get the best signal, and this 3D FPV setup using two cameras.

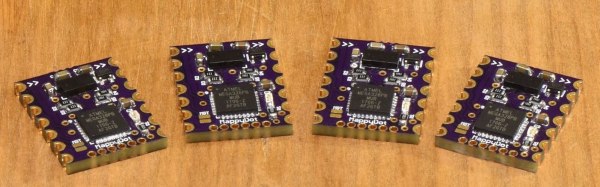

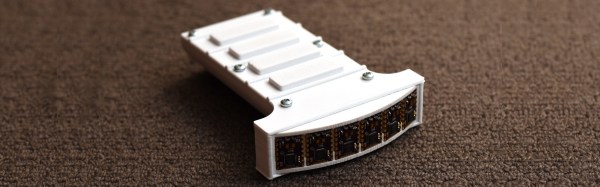

He uses a very clever arrangement of six sensors to get four virtual strings. Each sensor scans a 25-degree field of view. Three adjacent sensors are used to define a string, with the string being in the overlap of the outer two of those sensors. The middle sensor is used for the distance data.

He uses a very clever arrangement of six sensors to get four virtual strings. Each sensor scans a 25-degree field of view. Three adjacent sensors are used to define a string, with the string being in the overlap of the outer two of those sensors. The middle sensor is used for the distance data.