One of the joys of electronics as a hobby is how easy it is to get parts. Literally millions of parts are available from thousands of suppliers and hundreds of distributors, and everyone competes with each other to make it as easy as possible to put together an order from a BoM. If you need it, somebody probably has it.

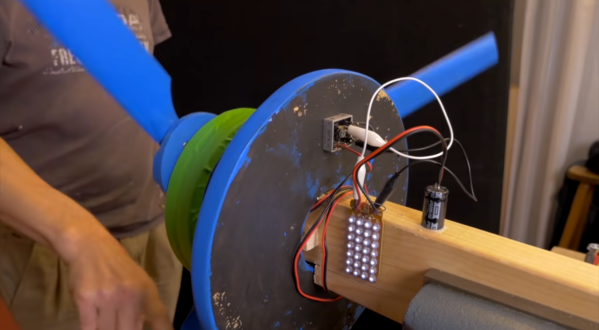

But what do you do when you need a part that doesn’t exist anymore, and even when it did was only produced in small numbers? Easy – you create it yourself. That’s just what [Mike Gardi] did with this unique motorized rotary switch he needed to complete his replica of a 1960s computer trainer. We covered his build of the Minivac 601, a trainer from the early computer age that let experimenters learn the ropes of basic digital logic. It used mostly relays, lamps, and switches connected by jumpers, but it had one critical component – a rotary control that was used for input and, with the help of a motor, as an output indicator.

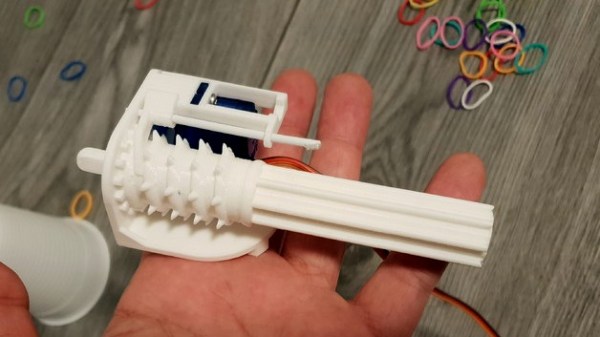

[Mike]’s version of the switch is as faithful to the original as possible, at least in terms of looks. The parts are mostly 3D-printed, with 16 reed switches embedded in the walls and magnets placed in the rotor. The motor to operate the rotor is a simple gear motor mounted to a hinged bracket; when the rotor needs to move, a solenoid pulls the motor’s friction drive wheel up against the rotor.

The unique control slots right into the Minivac replica and really completes the look and feel. Hats off to [Mike] for a delightful replica of a lost bit of computer history and the dedication to see it through to completion.

Continue reading “Minivac 601 Replica Gets A Custom Motorized Rotary Switch”