Not every piece of technology or software can succeed, even with virtually unlimited funding and marketing. About the same number of people are still playing Virtual Boys as are using Google Plus, for example. In recent memory, the Windows Phone occupies the same space as these infamous failures, potentially because it was late to the smartphone game but primarily because no one wanted to develop software for it. But now, you can run Android apps on Windows Phones now. (Google Translate from German)

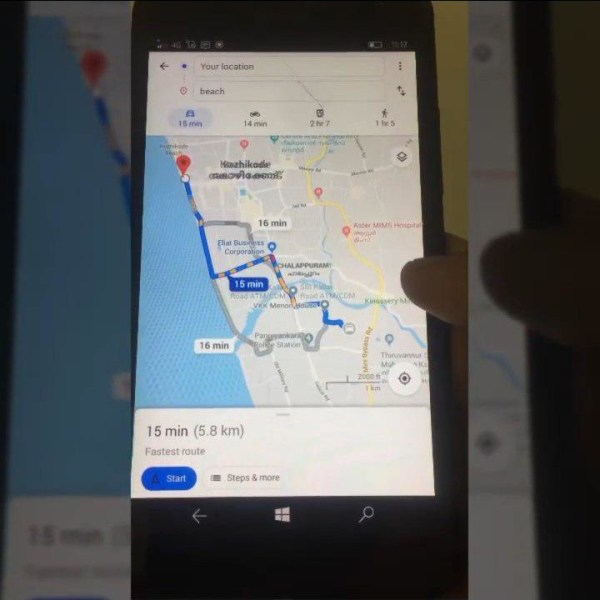

To be clear, this doesn’t support all Android apps or all Windows Phones, and it will take a little bit of work to get it set up at all. But if you still have one laying around you might want to go grab it. First you’ll need to unlock the phone, and then begin sending a long string of commands to the device which sends the required software to the device. If that works, you can begin loading Android apps on the phone via a USB connection to a PC.

This hack came to us via Windows Central and Reddit. It seems long and involved but if you have any experience with a command line you should be fine. It’s an interesting way to get some more use out of your old Windows Phone if it’s just gathering dust in a closet somewhere. If not, don’t worry; Windows Phones were rare even when they were at their most popular. We could only find one project in our archives that uses one, and that was from 2013.