Among the many science toys that have fallen out of fashion since we started getting nervous around things like mercury, chlorinated hydrocarbons, and radiation is the spinthariscope, which let people watch the flashes of light on a phosphor screen as a radioactive material decayed behind it. In fact, they hardly expose their viewers to any radiation, which makes [stoppi]’s homemade spinthariscope much safer than it might first seem.

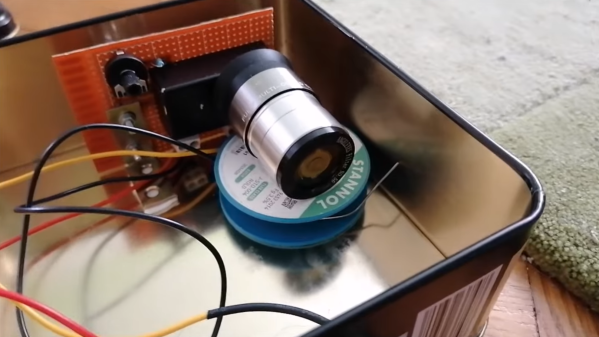

[Stoppi] built the spinthariscope out of the eyepiece of a telescope, a silver-doped zinc sulfide phosphor screen, and the americium-241 capsule from a smoke detector. A bit of epoxy holds the phosphor screen in the lens’s focal plane, and the americium capsule is mounted on a light filter and screwed onto the eyepiece. Since americium is mainly an alpha emitter, almost all of the radiation is contained within the device.

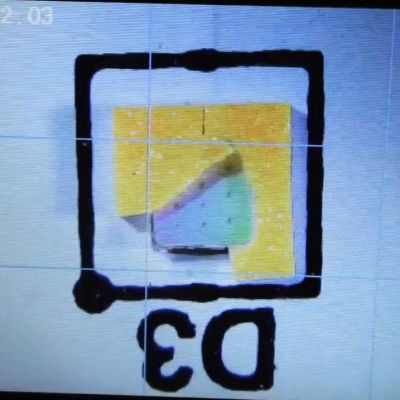

After sitting in a dark room for a few minutes to let one’s eyes adjust, it’s possible to see small flashes of light as alpha particles hit the phosphor screen. The flashes were too faint for a smartphone camera to pick up, so [stoppi] mounted it in a light-tight metal box with a photomultiplier and viewed the signal on an oscilloscope, which revealed many small pulses.

Continue reading “Watching Radioactive Decay With A Homemade Spinthariscope”