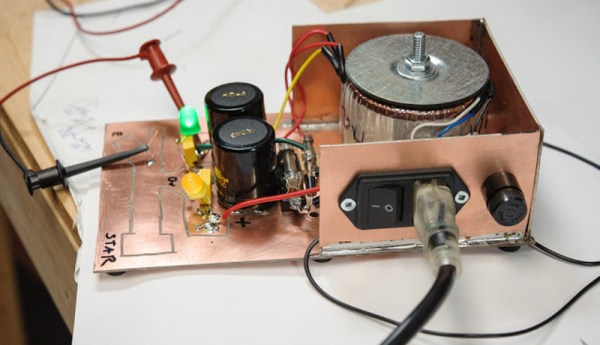

[Tony] built a high-efficiency power supply for Nixie tube projects. But that’s not what this post is about, really.

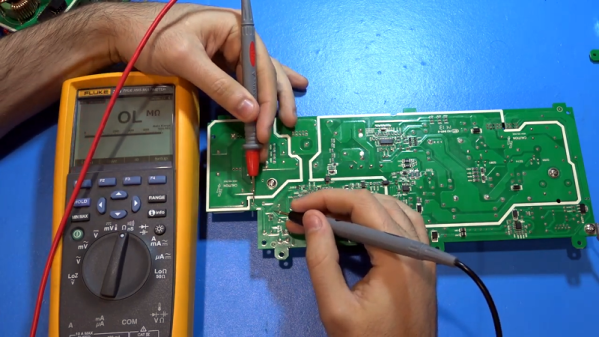

As you read through [Tony]’s extremely detailed post on Hackaday.io, you’ll be reading through an object lesson in electronic design that covers the entire process, from the initial concept – a really nice, reliable 170 V power supply for Nixie tubes – right through to getting the board manufactured and setting up a Tindie store to sell them.

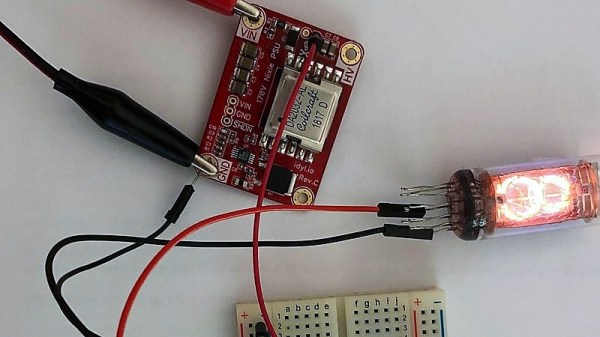

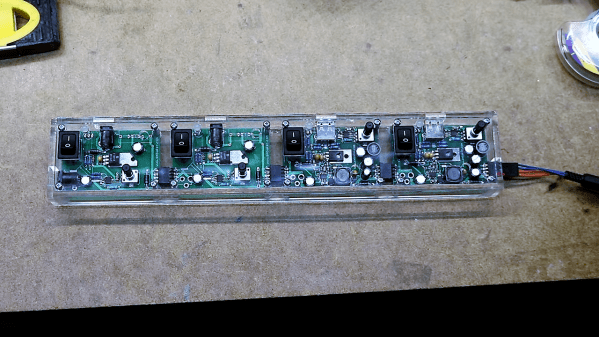

[Tony] saw the need for a solid, well-made high-voltage supply, so it delved into data sheets and found a design that would work – as he points out, no need to reinvent the wheel. He built and tested a prototype, made a few tweaks, then took PCBWay up on their offer to stuff 10 boards for a mere $88. There were some gotchas to work around, but he got enough units to test before deciding to ramp up to production.

Things got interesting there; ordering full reels of parts like flyback transformers turned out to be really important and not that easy, and the ongoing trade war between China and the US resulted in unexpected cost increases. But FedEx snafus notwithstanding, the process of getting a 200-unit production run built and shipped seemed remarkably easy. [Tony] even details his pricing and marketing strategy for the boards, which are available on Tindie and eBay.

We learned a ton from this project, not least being how hard it is for the little guy to make a buck in this space. And still, [Tony]’s excellent documentation makes the process seem approachable enough to be attractive, if only we had a decent idea for a widget.