Most video games, whether on console or PC, have standardized around either a keyboard and mouse or an analog controller of some sort, with very little differences between various offerings from the likes of Sony, Microsoft, Nintendo, or even Valve. This will get most of us through almost all video games, but for those looking to take their gameplay up a notch or who are playing much more complex games, certain specialized controllers are available, but they might not meet everyone’s specific needs. Thanks to this custom, modular keyboard anyone should be able to make exactly the controller they need.

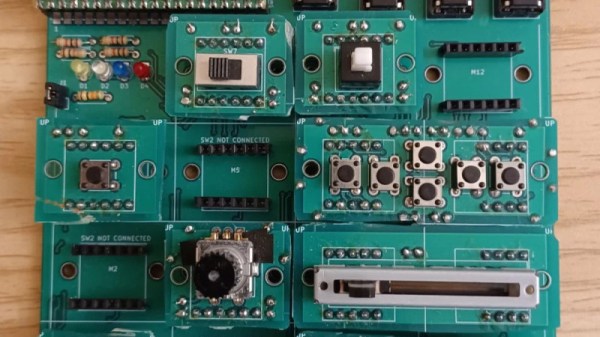

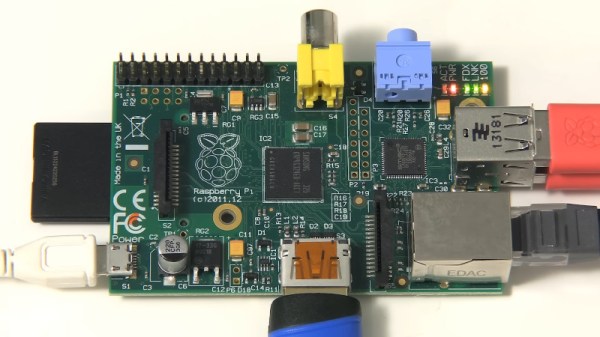

The device features a grid of 15 interfaces where modules like buttons, potentiometers, encoders, and joysticks can be placed. Each module can be customized to a significant extent on their own, and they can be placed anywhere on the grid. The modules themselves can be assigned to trigger keyboard presses or gamepad motions depending on the needs of the user. A Raspberry Pi handles the inputs and translates them to the computer, so in that regard it functions no differently than a standard keyboard or gamepad would. Programming is done by sending commands via a USB serial port, with the ability to save various configurations as well.

The modular controller is open-source in terms of hardware and software, with easy assembly using through-hole components and a customizable 3D printed cover for anyone looking to make their own. The project’s creator [Daniel] had flight simulators in mind when designing the device, which often benefit from having more specialized controllers, but any game with lots of specific inputs from Starcraft to League of Legends could benefit from a custom controller or keyboard like this. Flight simulators are more often the targets of specialized and unique controls, though, like this custom yoke or this physical control panel.