These days, everything’s got a clock in it, and a good proportion of those clocks are automatically syncronized to high-accuracy Internet time servers. Back in the past, things weren’t so easy. Often, institutions that required accurate time would use a single highly-accurate primary clock to drive a series of secondary clocks around a facility. Without the primary clock, the secondary clock has no signal to drive it. [Oleksii Samorukov] had just such a clock, and whipped up a controller to stand in for timekeeping duty.

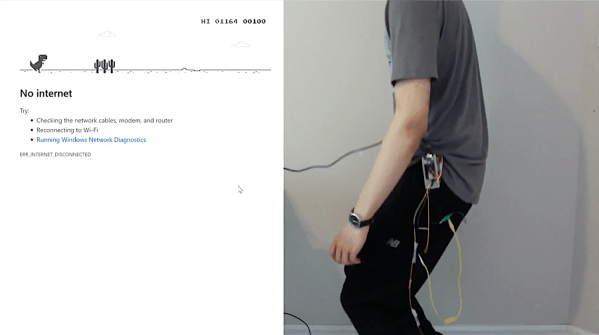

The secondary clock in question is a Pragotron PJ 27, which requires regular 12V signals of alternating polarity in order to keep time. To handle this job, [Oleksii] decided to use an ESP32 in combination with an L298N motor controller. The L298N is an H-bridge driver chip, allowing it to easily supply the 12V signals in alternating polarities where required. To ensure the system keeps accurate time, the ESP32 regularly queries an NTP time server over WiFi.

It’s a tidy build, and one that brings this attractive 1960s timepiece into the modern era. We’d love to have such a stylish, well-built clock in our own home, too. Of course, if you want really accurate time, building a GPS clock is a great option, too!

[Thanks to Irregular Shed for the tip!]