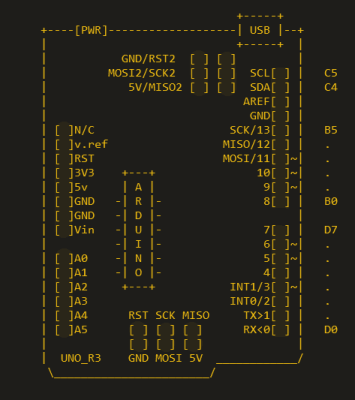

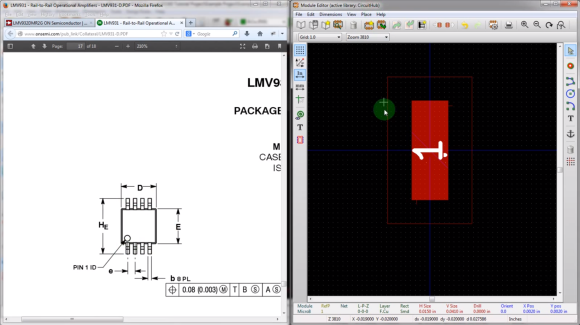

When I saw this year’s Supercon Vectorscope badge, I decided that I had to build one for myself. Since I couldn’t attend in-person, I immediately got the PCBs and parts on order. Noting that the GitHub repository only had the KiCad PCB file and not the associated schematics and project file, I assumed this was because everyone was in a rush during the days leading up to Supercon weekend. I later learned, however, that there really wasn’t a KiCad project — the original design was done in Circuit Maker and the PCB was converted into KiCad. I thought, “how hard can this be?” and decided to try my hand at completing the KiCad project.

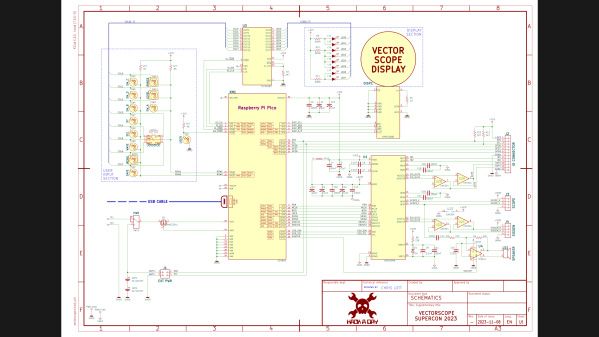

Fortunately I didn’t have to start from scratch. The PCB schematics were provided, although only as image files. They are nicely laid out and fortunately don’t suffer the scourge of many schematics these days — “visual net lists” that are neither good schematics nor useful net lists. To the contrary, these schematics, while having a slightly unorthodox top to bottom flow, are an example of good schematic design. Continue reading “Vectorscope KiCad Redrawing Project”