Not all glues are created equal; or rather, not every glue is good for every application. But how is one to know which glue to use in which kinds of joints? The answer to that is not always clear, but solid numbers on the comparative strength of different glues are a great place to start.

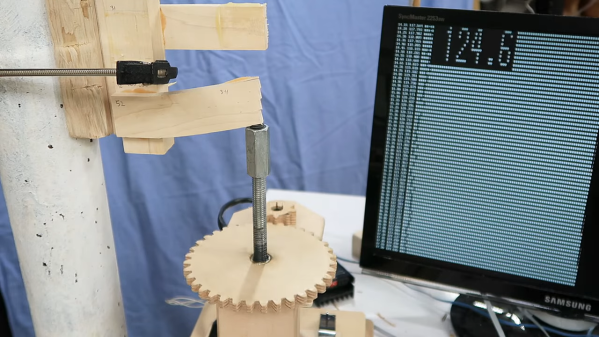

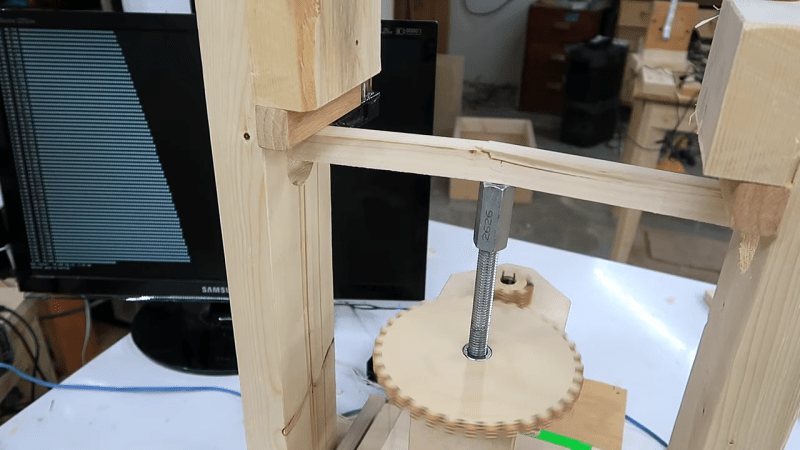

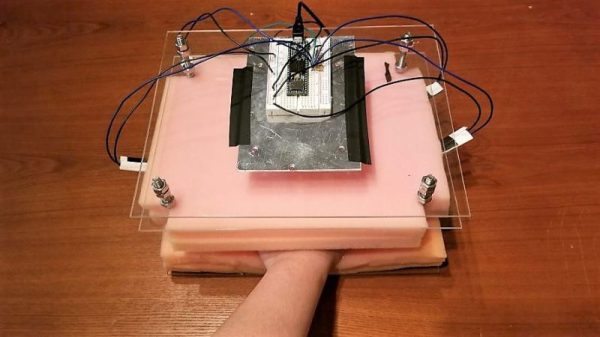

To quantify what can ordinarily be a somewhat subjective process, there’s probably no one better than woodworker and hacker [Matthias Wandel], equipped as he is with his DIY strength-tester. Using its stepper-driven power to blast apart glued lap joints, [Matthias] measured the yield point of the various adhesives using a strain gauge connected to a Raspberry Pi.

His first round of tests had some interesting results, including the usually vaunted construction adhesive ending up in a distant last place. Also performing poorly, at least relative to its reputation and the mess it can cause, was the polyurethane-based Gorilla Glue. A surprise standout in overall strength was hot glue, although that seemed to have a sort of plastic yield mode. Ever the careful empiricist, [Matthias] repeated his tests using hardwoods, with remarkably different results; it seems that glues really perform better with denser wood. He also repeated a few tests to make sure every adhesive got a fair shake. Check out the video below for the final results.

It’s always good to see experiments like this that put what we often take for granted to the test. [John] over at the Project Farm channel on YouTube does this kind of stuff too, and even did a head-to-head test of epoxy adhesives.

Continue reading “Raspberry Pi Test Stand Tells You Which Glues To Use”