Lots of things beep these days. Washing machines, microwaves, fridge — even drill battery chargers. If you’re on Team Makita, it turns out you can actually change the melody of your charger’s beep, thanks to a project from [Real-Time-Kodi].

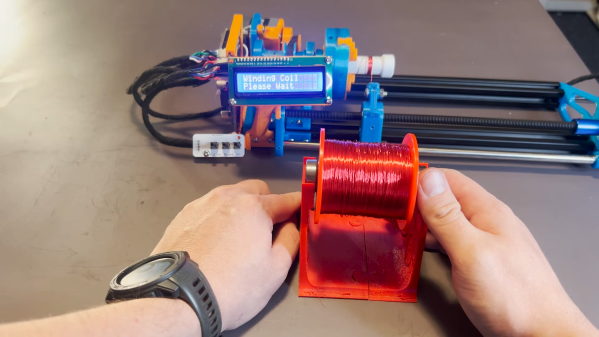

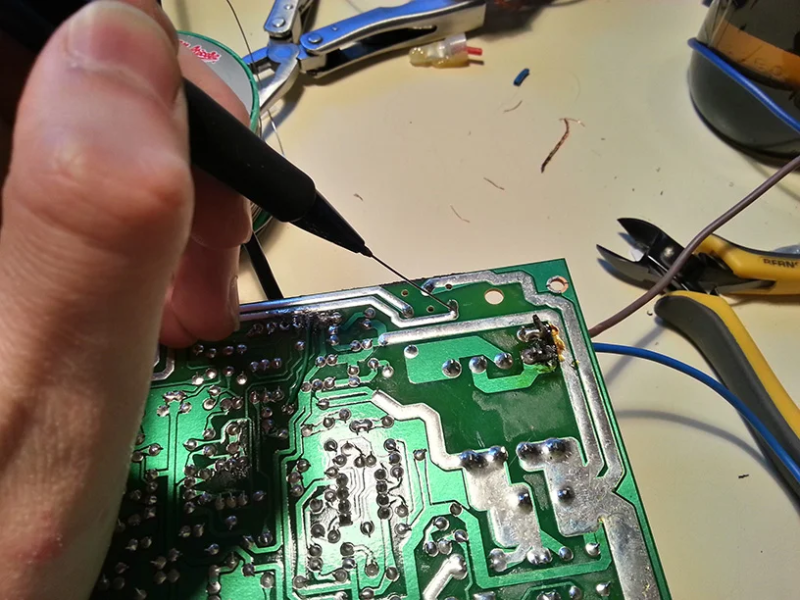

The hack is for the Makita DR18RC charger, and the implementation of the hack is kind of amusing. [Real-Time-Kodi] starts by cutting the trace to the buzzer inside the charger. Then, an Arduino is installed inside the charger, hooked up to the buzzer itself and the original line that was controlling it. When it detects the charger trying to activate the buzzer, it uses this as a trigger to play its own melody on the charger instead. The Arduino also monitors the LEDs on the charger in order to determine the current charge state, and play the appropriate jingle for the situation.

It’s an amusing hack, and one that could certainly confuse the heck out of anyone expecting the regular tones out of their Makita charger. It also shows that the simple ways work, too — there was no need to dump any firmware or decompile any code.

Continue reading “Change The Jingle In Your Makita Charger Because You Can”