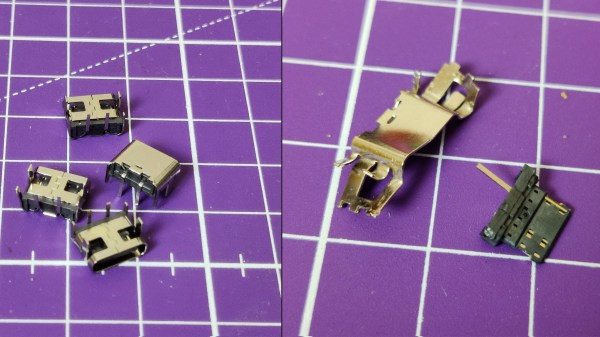

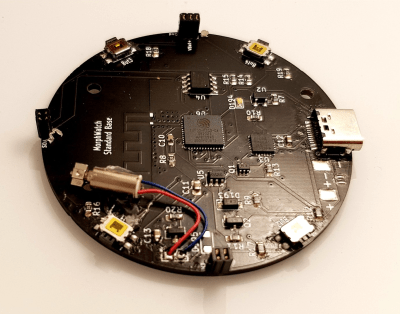

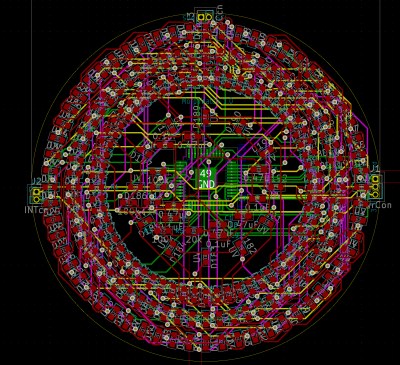

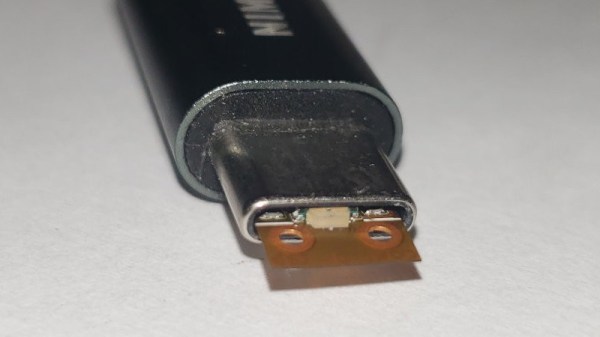

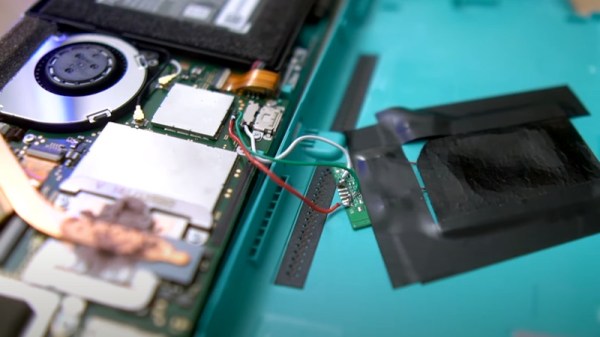

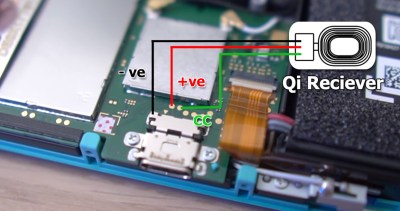

[Peng Zhihui] seems to have found some spare time and energy to crack out another sweet robot build, this time it’s a much smaller, and cuter emoji-bot (Original GitHub Link,) with the usual production-ready levels of attention to detail. With a lot of fine details in the 3D printed models, this is one for SLS printing in nylon, but that can be done for a reasonable outlay, in China at least. The electronics package consists of a few full custom, and tiny, PCBs designed with Altium Designer, with off-the-shelf modules for the circular LCD and camera. The main board hosts an STM32F405 and deals with the display and SD card, The reason for this choice of STM32 was due to the requirement for connecting to an external USB3300 high-speed USB PHY. There is a sensor PCB which handles the gesture sensor, a USB hub, MPU6050 9-axis sensor, and also the USB camera module. This board attaches to the USB-C connector in the base, via a FFC cable, allowing the robot to rotate on its base.

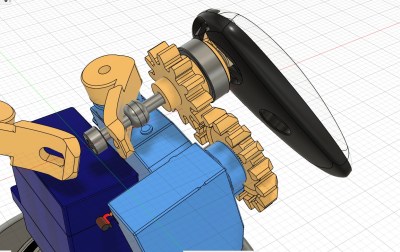

[Peng] clearly has exacting standards as to how things should work, and we guess wanted to have the arms back-driveable in a way that enabled the host computer to track and record the motor positions for replaying later on. The connection back to the controller is via I2C, allowing all five servos to hang on the same bus, saving previous resources. Smart! Getting a processor and motor driver in such a tiny space was a bit of challenge, but a walk in the park for [Peng] as is demonstrates in the video embedded below (We believe English subtitles are pending!) The arm mechanism is particularly interesting, and rather elegantly executed, and he does seem rather proud of this part of the design, and so he should! Like with [Peng’s] other projects, there is a lot to see, and plenty of scope for feature explosion. It was nice to see the ‘bot being used as an input device, not only with gesture sensing via the dedicated sensor, but also using the camera with OpenCV to track user posture and act accordingly. This thing could act as genuinely useful AI device, as was a being darn cute at the same time!

We know you come to Hackaday for your cute robot fix, and we’re not going to disappoint. Here’s a cute robot lamp, an obligatory spot (a robot dog) type project, and if you’re more of a cat person, then we got that base covered as well.

Continue reading “ElectronBot: A Sweet Mini Desktop Robot That Ticks All The Boxes”