The Raspberry Pi Compute Module 4 has a built-in WiFi antenna, but that doesn’t mean it will work well for you – the physical properties of the carrier board impact your signal quality, too. [Avian] decided to do a straightforward test – measuring WiFi RSSI changes and throughput with a few different carrier boards. It appears that the carriers he used were proprietary, but [Avian] provides sketches of how the CM4 is positioned on these.

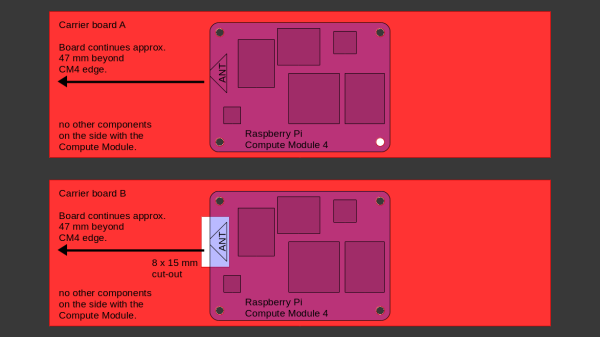

There’s two recommendations for making WiFi work well on the CM4 – placing the module’s WiFi antenna at your carrier PCB’s edge, and adding a ground cutout of a specified size under the antenna. [Avian] made tests with three configurations in total – the CMIO4 official carrier board which adheres to both of these rules, carrier board A which adheres to neither, and carrier board B which seems to be a copy of board A with a ground cutout added.

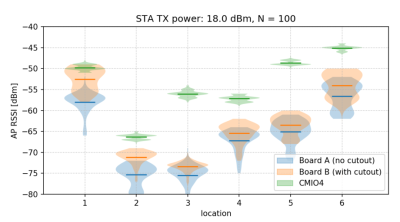

After setting up some test locations and writing a few scripts for ease of testing, [Avian] recorded the experiment data. Having that data plotted, it would seem that, while presence of an under-antenna cutout helps, it doesn’t affect RSSI as much as the module placement does. Of course, there’s way more variables that could affect RSSI results for your own designs – thankfully, the scripts used for logging are available, so you can test your own setups if need be.

After setting up some test locations and writing a few scripts for ease of testing, [Avian] recorded the experiment data. Having that data plotted, it would seem that, while presence of an under-antenna cutout helps, it doesn’t affect RSSI as much as the module placement does. Of course, there’s way more variables that could affect RSSI results for your own designs – thankfully, the scripts used for logging are available, so you can test your own setups if need be.

If you’re lucky to be able to design with a CM4 in mind and an external antenna isn’t an option for you, this might help in squeezing out a bit more out of your WiFi antenna. [Avian]’s been testing things like these every now and then – a month ago, his ESP8266 GPIO 5V compatibility research led to us having a heated discussion on the topic yet again. It makes sense to stick to the design guidelines if WiFi’s critical for you – after all, even the HDMI interface on Raspberry Pi can make its own WiFi radio malfunction.

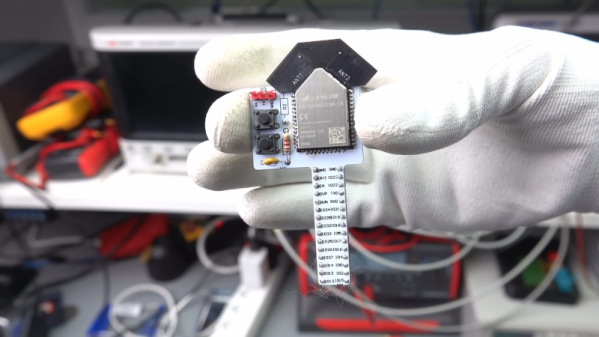

At its core, the project uses an ESP32 and the

At its core, the project uses an ESP32 and the