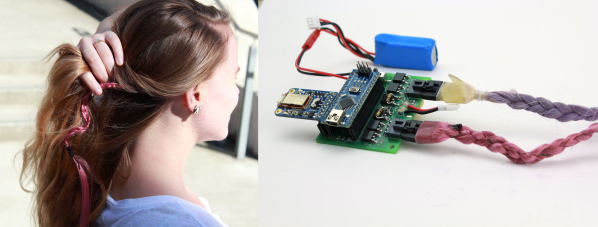

Most of what we see on the wearable tech front is built around traditional textiles, like adding turn signals to a jacket for safer bike riding, or wiring up a scarf with RGB LEDs and a color sensor to make it match any outfit. Although we’ve seen the odd light-up hair accessory here and there, we’ve never seen anything quite like these Bluetooth-enabled, shape-shifting, touch-sensing hair extensions created by UC Berkeley students [Sarah], [Molly], and [Christine].

HairIO is based on the idea that hair is an important part of self-expression, and that it can be a natural platform for sandboxing wearable interactivity. Each hair extension is braided up with nitinol wire, which holds one shape at room temperature and changes to a different shape when heated. The idea is that you could walk around with a straight braid that curls up when you get a text, or lifts up to guide the way when a friend sends directions. You could even use the braid to wrap up your hair in a bun for work, and then literally let it down at 5:00 by sending a signal to straighten out the braid. There’s a slick video after the break that demonstrates the possibilities.

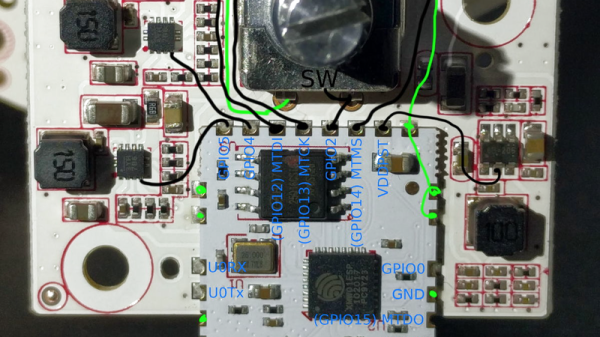

HairIO is controlled with an Arduino Nano and a custom PCB that combines the Nano, a Bluetooth module, and BJTs that drive the braid. Each braid circuit also has a thermistor to keep the heat under control. The team also adapted the swept-frequency capacitive sensing of Disney’s Touché project to make HairIO extensions respond to complex touches. Our favorite part has to be that they chalked some of the artificial tresses with thermochromic pigment powder so they change color with heat. Makes us wish we still had our Hypercolor t-shirt.

Nitinol wire is nifty stuff. You can use it to retract the landing gear on an RC plane, or make a marker dance to Duke Nukem.

Continue reading “HairIO: An Interactive Extension Of The Self”