There are many ways in which one’s youth can be misspent, most of which people wish they’d done when they get older and look back on their own relatively boring formative years. I misspent my youth pulling TV sets out of dumpsters and fixing them or using their parts in my projects. I recognise with hindsight that there might have been a few things I could have done with more street cred, but for me, it was broken TVs. Continue reading “Understanding A Bit About Noise Can Help You Go A Long Way”

Year: 2020

Neat And Tidy USB-C Conversions For Legacy Devices

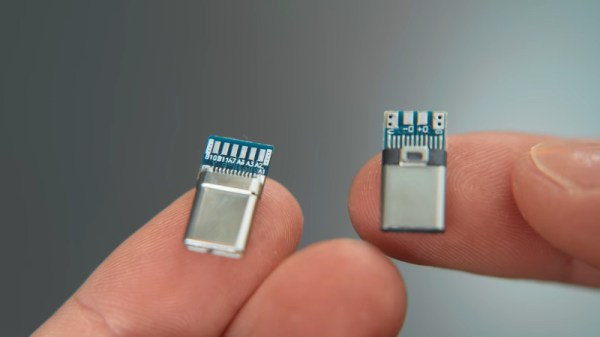

USB-C has been on the market for a good few years now, and it’s finally starting to take over. Many new laptops only come with the newer port, making it difficult to use legacy USB-A devices. [Matt] doesn’t like mucking about with dongles and hubs, so set about converting some older hardware to the new standard. (Video, embedded below.)

[Matt] first set about hacking a Logitech wireless mouse dongle, peeling apart the original USB A connector to gain access to the PCB inside. A USB C breakout board is then sourced, and the relevant pins in the USB-C connector are soldered to the original USB-A connector pads. Unfortunately, the breakout board is configured as a host device, unsuitable for peripherals. Replacing a pull-up resistor with a pull-down on the VCONN and CC1 pins rectifies this. With the mod done, the mouse enumerates and is fully functional over USB-C. A little Sugru is then used to wrap everything up neatly.

[Matt] then progresses through several other similar mods to other hardware, sharing useful tips on how to make things as neat and useful as possible. It’s a tidy hack that could make your user experience with a new laptop much less painful. USB-C mods are becoming more common, and we’ve seen plenty done to soldering irons thanks to the Power Delivery spec.

Continue reading “Neat And Tidy USB-C Conversions For Legacy Devices”

Open Source Raman Spectrometer Is Cheaper, But Not Cheap

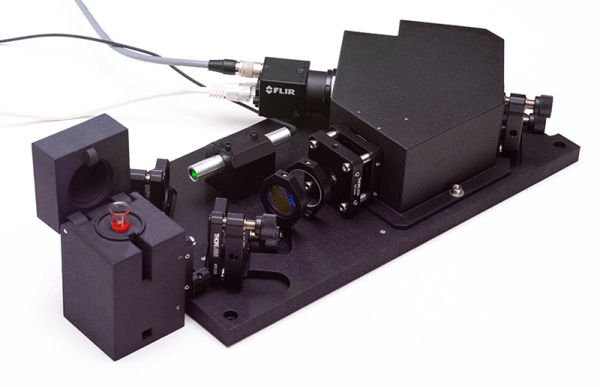

Raman spectrography uses the Raman scattering of photons from a laser or other coherent light beam to measure the vibrational state of molecules. In chemistry, this is useful for identifying molecules and studying chemical bonds. Don’t have a Raman spectroscope? Cheer up! Open Raman will give you the means to build one.

The “starter edition” replaces the initial breadboard version which used Lego construction, although the plans for that are still on the site, as well. [Luc] is planning a performance edition, soon, that will have better performance and, presumably, a greater cost.

Continue reading “Open Source Raman Spectrometer Is Cheaper, But Not Cheap”

Alexa, Shoot Me Some Chocolate

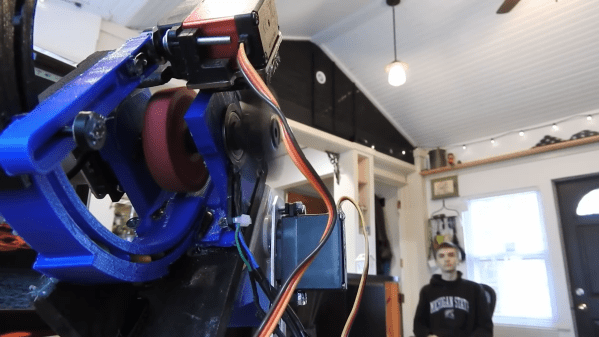

[Harrison] has been busy finding the sweeter side of quarantine by building a voice-controlled, face-tracking M&M launcher. Not only does this carefully-designed candy launcher have control over the angle, direction, and velocity of its ammunition, it also locates and locks on to targets by itself.

Here comes the science: [Harrison] tricked Alexa into thinking the Raspberry Pi inside the machine is a smart TV named [Chocolate]. He just tells an Echo to increase the volume by however many candy-colored projectiles he wants launched at his face. Simply knowing the secret language isn’t enough, though. Thanks to a little face-based security, you pretty much have to be [Harrison] or his doppelgänger to get any candy.

The Pi takes a picture, looks for faces, and rotates the turret base in that direction using three servos driven by Arduino Nanos. Then the Pi does facial landmark detection to find the target’s mouth hole before calculating the perfect parabola and firing. As [Harrison] notes in the excellent build video below, this machine uses a flywheel driven by a DC motor instead of being spring-loaded. M&Ms travel a short distance from the chute and hit a flexible, spinning disc that flings them like a pitching machine.

We would understand if you didn’t want your face involved in a build with Alexa. It’s okay — you can still have a voice-controlled candy cannon.

Free Cloud Data Logging Courtesy Of Google

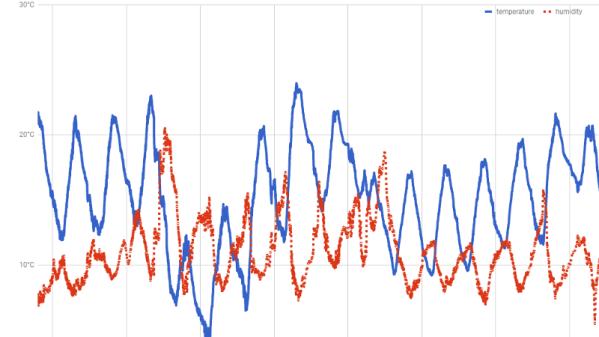

Pushing all of your data into “The Cloud” sounds great, until you remember that what you’re really talking about is somebody else’s computer. That means all your hard-crunched data could potentially become inaccessible should the company running the service go under or change the rules on you; a situation we’ve unfortunately already seen play out.

Which makes this project from [Zoltan Doczi] and [Róbert Szalóki] so appealing. Not only does it show how easy it can be to shuffle your data through the tubes and off to that big data center in the sky, but they send it to one of the few companies that seem incapable of losing market share: Google. But fear not, this isn’t some experimental sensor API that the Big G will decide it’s shutting down next Tuesday in favor of a nearly identical service with a different name. All your precious bits and bytes will be stored in one of Google’s flagship products: Sheets.

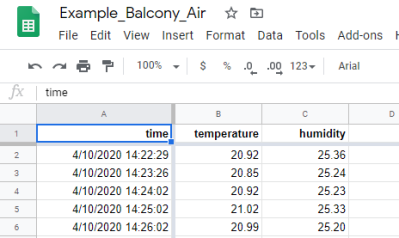

It turns out that Sheets has a “Deploy as Web App” function that will spit out a custom URL that clients can use to access the spreadsheet data. This project shows how that feature can be exploited with the help of a little Python code to push data directly into Google’s servers from the Raspberry Pi or other suitably diminutive computer.

It turns out that Sheets has a “Deploy as Web App” function that will spit out a custom URL that clients can use to access the spreadsheet data. This project shows how that feature can be exploited with the help of a little Python code to push data directly into Google’s servers from the Raspberry Pi or other suitably diminutive computer.

Here they’re using a temperature and humidity sensor, but the only limitation is your imagination. As an added bonus, the chart and graph functions in Sheets can be used to make high-quality visualizations of your recorded data at no extra charge.

You might be wondering what would happen if a bunch of hackers all over the world started pushing data into Sheets every few seconds. Honestly, we don’t know. The last time we showed how you could interact with one of their services in unexpected ways, Google announced they were retiring it on the very same day. It was probably just a coincidence, but to be on the safe side, we’d recommend keeping the update frequency fairly low.

Back in 2012, before the service was even known as Google Sheets, we covered how you could do something very similar by manually assembling HTTP packets containing your data. We’d say this validates the concept for long-term data storage, but clearly the methodology has changed considerably in the intervening years. Somebody else’s computer, indeed.

A Backpack That Measures Your Heart Rate

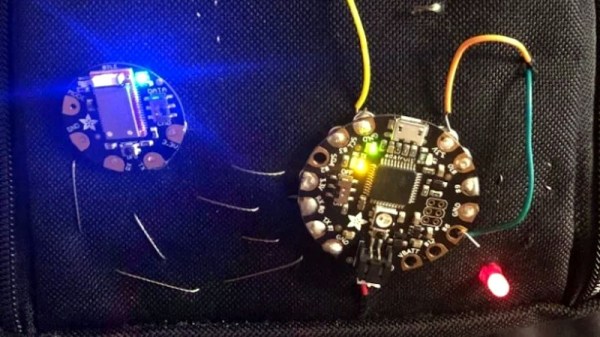

It’s interesting to see the different form-factors that people utilize for their portable biometric sensors. We’re seeing heart rate monitors and other biometric sensors integrated into watches, earbuds, headbands, sports bras, and all sorts of other garments and accessories. [Gabi] took an intriguing approach, integrating an electrocardiogram (ECG) into a backpack. This type of heart rate project is pretty popular here on Hackaday, so it was great running across [Gabi’s] design during our daily perusing for the new and exciting.

[Gabi] used an Adafruit FLORA, a BLE module, an ECG sensor from Bitalino, a few other ancillary components, and, of course, a backpack. We appreciate that she walked us through the list of stumblingblocks she came across and how she got around them. So much of the time in our excitement to share our projects we remove the gory details and only present the finished project when really, we learn most from all the things that didn’t work more so than the things that did. Finally, [Gabi] walks through the intricacies of the threading and the particular placement of the snap connectors to attach the circuit to the ECG electrodes. Things get pretty tricky, but luckily [Gabi] documents her project pretty meticulously with schematics, pictures, and early notice of pitfalls.

[Gabi] made sure to remind her readers that this is a prototype, not a medical device. She also brought up electrical safety. Biometric devices such as ECGs need to include a strict set of isolation circuits to prevent potential harm to the user. Fortunately, there are a few well-characterized methods to accomplish this.

So thanks for a really cool project, [Gabi], and to our readers, why not enjoy some of our other ECG projects while you’re at it?

Side-Channel Attack Turns Power Supply Into Speakers

If you work in a secure facility, the chances are pretty good that any computer there is going to be stripped to the minimum complement of peripherals. After all, the fewer parts that a computer has, the fewer things that can be turned into air-gap breaching transducers, right? So no printers, no cameras, no microphones, and certainly no speakers.

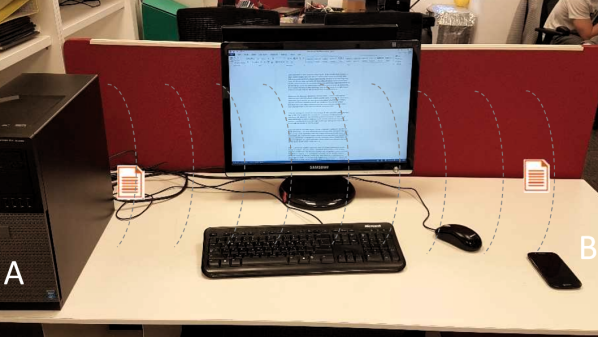

Unfortunately, deleting such peripherals does you little good when [Mordechai Guri] is able to turn a computer power supply into a speaker that can exfiltrate data from air-gapped machines. In an arXiv paper (PDF link), [Guri] describes a side-channel attack of considerable deviousness and some complexity that he calls POWER-SUPPLaY. It’s a two-pronged attack with both a transmitter and receiver exploit needed to pull it off. The transmitter malware, delivered via standard methods, runs on the air-gapped machine, and controls the workload of the CPU. These changes in power usage result in vibrations in the switch-mode power supply common to most PCs, particularly in the transformers and capacitors. The resulting audio frequency signals are picked up by a malware-infected receiver on a smartphone, presumably carried by someone into the vicinity of the air-gapped machine. The data is picked up by the phone’s microphone, buffered, and exfiltrated to the attacker at a later time.

Yes, it’s complicated, requiring two exploits to install all the pieces, but under the right conditions it could be feasible. And who’s to say that the receiver malware couldn’t be replaced with the old potato chip bag exploit? Either way, we’re glad [Mordechai] and his fellow security researchers are out there finding the weak spots and challenging assumptions of what’s safe and what’s vulnerable.

Continue reading “Side-Channel Attack Turns Power Supply Into Speakers”