At the heart of all computers is a clock, a dedicated timepiece ensuring that all of the parts of the computer are synchronized and can work together to execute the instructions that the computer receives. Clock speeds for most modern off-the-shelf computers and smartphones operate around a billion cycles per second, and even clocks that tick at a human-dizzying speed of a million times per second have been around since at least the 1970s. But there’s no reason a computer can’t run at a much slower speed, as [Greg] demonstrates in this video where he slows down a 6502 processor to a single clock cycle per second.

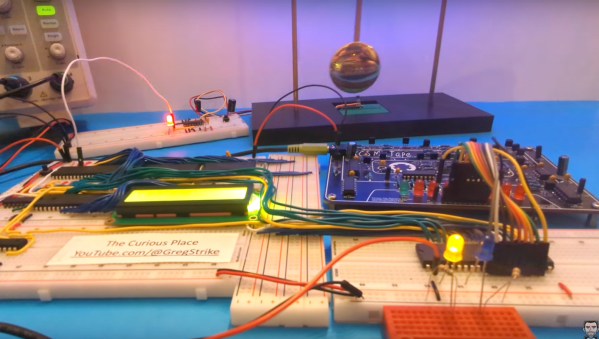

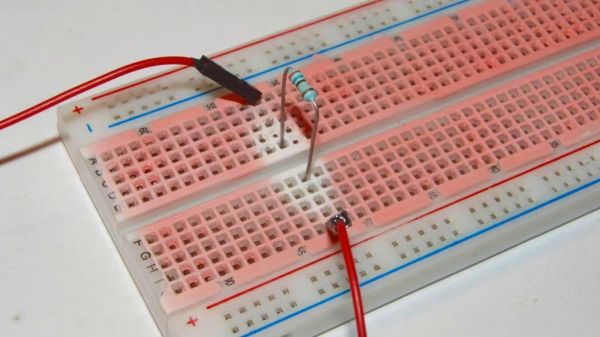

To reduce the clock speed from the megahertz range down to a single hertz or single clock cycle per second, [Greg] is using the pendulum from an actual clock. He attaches a small magnet to the bottom of the pendulum which is counted by a sensor as it swings past. Feeding that pulse into a monostable conditioner yields a clock signal which is usable for one of his 6502-based computers, and at this extremely slow rate, it’s possible to see the operation of a lot of the computers’ inner workings a step at a time. In fact, he optimized the computer’s operation as this slow speed let him see some inefficiencies in the program he was running.

It helps if your processor is static, of course. Older CPUs with dynamic storage for registers and some with limited-range PLLs would not work with this technique. The 8080A, for example, required a clock of at least 500 kHz.

Not only can this computer use a pendulum clock as the basis for its internal clock, but [Greg] also rigged up a mechanism to use a heartbeat. Getting in a little bit of exercise to increase his heart rate first will noticeably increase the computer’s speed. And, if you’re looking to get a deeper glimpse into the inner workings of a computer, we’d recommend looking at one which forgoes transistors in favor of relays.