We’ve talked about Ethernet basics, and we’ve talked about equipment you will find with Ethernet. However, that’s obviously not all – you also need to know how to add Ethernet to your board and to your microcontroller. Such low-level details are harder to learn casually than the things we talked about previously, but today, we’re going to pick up the slack.

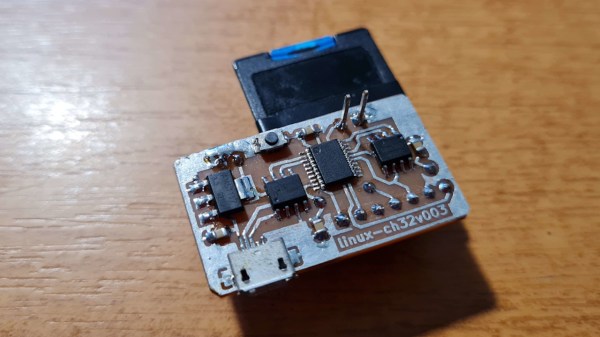

You might also have some very fair questions. What are the black blocks near Ethernet sockets that you generally will see on boards, and why do they look like nothing else you see on circuit boards ever? Why do some boards, like the Raspberry Pi, lack them altogether? What kind of chip do you need if you want to add Ethernet support to a microcontroller, and what might you need if your microcontroller claims to support Ethernet? Let’s talk.

Transformers Make The Data World Turn

One of the Ethernet’s many features is that it’s resilient, and easy to throw around. It’s also galvanically isolated, which means you don’t need a ground connection for a link either – not until you want a shield due to imposed interference, at which point, it might be that you’re pulling cable inside industrial machinery. There are a few tricks to Ethernet, and one such fundamental Ethernet trick is transformers, known as “magnetics” in Ethernet context.

Each pair has to be put through a transformer for the Ethernet port to work properly, as a rule. That’s the black epoxy-covered block you will inevitably see near an Ethernet port in your device. There are two places on the board as far as Ethernet goes – before the transformer, and after the transformer, and they’re treated differently. After the transformer, Ethernet is significantly more resilient to things like ground potential differences, which is how you can wire up two random computers with Ethernet and not even think about things like common mode bias or ground loops, things we must account for in audio, or digital interfaces that haven’t yet gone optical somehow.

Continue reading “Ethernet For Hackers: Transformers, MACs And PHYs”