We see a huge variety of human-computer interface devices here at Hackaday, and among them are some exceptionally elegant designs. Of those that use key switches though, the vast majority employ off the shelf components made for commercial keyboards or similar. It makes sense to do this, there are some extremely high quality ones to be had.

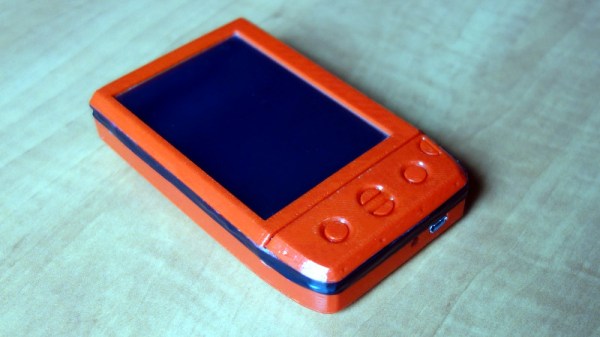

Sometimes though we are shown designs that go all the way in creating their key switches from the ground up. Such an example comes from [Brandon Rice], and it a particularly clever button design because of its use of laser cutting to achieve a super-slim result. He’s made a sandwich of plywood with the key mechanisms formed in a spiral cut on the top layer. He’s a little sketchy on the exact details of the next layer, but underneath appears to be a plywood spacer surrounding a silicone membrane with conductive rubber taken from a commercial keyboard. Beneath that is copper tape on the bottom layer cut to an interweaving finger design for the contacts. An Adafruit Trinket Pro provides the brains and a USB interface, and the whole device makes for an attractive and professional looking peripheral.

You can see the results in action as he’s posted a video, which we’ve included below the break.

Continue reading “Spiral Laser Cut Buttons Make A Super-Slim USB MIDI Board”