Name the countries that house a manned space program. In order of arrival in space, USSR/Russian Federation, United States of America, People’s Republic of China. And maybe one day, Denmark. OK, not the Danish government. But that doesn’t stop the country having a manned space program, in the form of Copenhagen Suborbitals. As the tagline on their website has it: “We’re 50 geeks building and flying our own rockets. One of us will fly into space“. If that doesn’t catch the attention of Hackaday readers, nothing will.

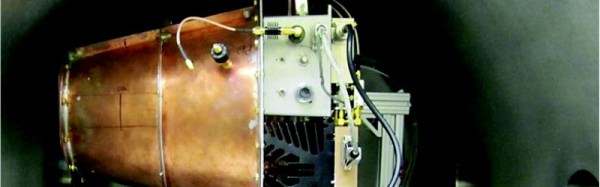

For their rocket testing they need a lot of video feeds, and for that they use cheap Chinese GoPro clones. The problem with these (and we suspect many other cameras) is that when subjected to the temperature and vibration of being strapped to a rocket, they cease to work. And since even nonprofit spaceflight engineers are experts at solving problems, they’ve ruggedized the cameras to protect them from vibration and provide adequate heatsinking.

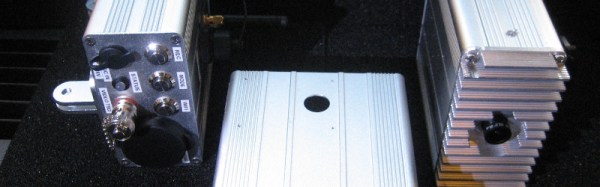

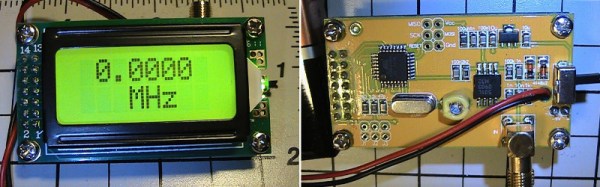

The heat issue is addressed by removing the camera case and attaching its metal chassis directly to a heatsink that forms the end of an extruded aluminium case. Vibration was causing the camera SD cards to come loose, so these are soldered into their sockets. Power is provided by a pair of 18650 cells with a switching regulator to provide internal power, and another to allow the unit to be charged from a wide range of input voltages. A PCB houses both the regulators and sockets for cable distribution. There is even a socket on top of the case to allow a small monitor to be mounted as a viewfinder. Along the way they’ve created a ruggedized camera that we think could have many applications far beyond rocket testing. Maybe they should sell kits!

We’ve covered Copenhagen Suborbitals before quite a few times, from their earliest news back in 2010, through a look at their liquid-fueled engine, to a recent successful rocket launch. We want to eventually report on this project achieving its aim.

Thanks [Morten] for the tip.

There are 480 LEDs in his display, and he addresses them through TLC5927 shift registers. Synchronisation is provided by a Hall-effect sensor and magnet to detect the start of each rotation, and the Teensy adjusts its pixel rate based on that timing. He’s provided extremely comprehensive documentation with code and construction details in the GitHub repository, including

There are 480 LEDs in his display, and he addresses them through TLC5927 shift registers. Synchronisation is provided by a Hall-effect sensor and magnet to detect the start of each rotation, and the Teensy adjusts its pixel rate based on that timing. He’s provided extremely comprehensive documentation with code and construction details in the GitHub repository, including